The Vietnam War

Forces Involved

The primary military organizations involved in the war were the United States Armed Forces and the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, pitted against the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) (commonly called the North Vietnamese Army, or NVA, in English-language sources) and the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF, more commonly known as the Viet Cong (VC) in English language sources), a South Vietnamese communist guerrilla force.

Origins

For much of the late 19th and early 20th century, what we know as Vietnam was a French colony called Indochina. In WWII, however, independence was declared by the communist leaders of Vietnam and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was established. This new nation survived for 20 days before the French regained control and led to the French Indochina War in 1946.

As the 1950s began, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was being financially supported and legitimized by communist leaders in China and The Soviet Union while the French forces were being supported by the UK and United States. By September 1950, the United States created a Military Assistance and Advisory Group (MAAG) to screen French requests for aid, advise on strategy, and train Vietnamese soldiers. In 1954, the United States’ investment in the French military effort reached $1 billion, making up about 80% of the cost of the war. May of that same year, however, saw the French surrender, granting freedom from colonial power to Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.

Civil War

At the Geneva Convention in 1954, Vietnam was split into two states at the 17th Parallel, North and South Vietnam with the hopes that by 1956, the two countries would be reunified by a statewide vote. In the North, Communist Ho Chi Mihn took power and in the South, anti-communist Emperor Bao Dai. Both sides wanted the same thing: a unified Vietnam. But while Ho and his supporters wanted a nation modeled after other communist countries, Bao and many others wanted a Vietnam with close economic and cultural ties to the West.

However, due to meddling by the United States CIA, around one million northerners, mainly minority Catholics, fled south, fearing persecution by the Communists who controlled the North. At the same time, 130,000 South Vietnam citizens were sent to North Vietnam for “regroupment training”. Tensions continued to arise both in the two states of Vietnam and between the outside forces hoping to control the outcome of the elections. Both sides rigged their elections in their own favor and in 1955 the South Vietnamese government declared itself an independent state, pushing aside Emperor Bao in favor of a new leader, President Ngo Dinh Diem. In the years that followed, there was much back and forth between the two states marked by violence and rapidly changing seizures of power.

American Escalation

By 1960, the Americans had adopted what they called the “Domino Theory” to justify their involvement in Vietnam’s conflict. The idea was that if any country “fell” to Communism, then the entire world was in danger of becoming communist. The Cold War was in full effect and fears of a Red Tide were ever present in the American consciousness. So in 1962, after a fact finding mission had been carried out the year prior, President John F. Kennedy sent some 9,000 troops to Vietnam, up from just 800 which had been the average in the decade before.

A year later, Diem was overthrown by his own generals just 3 weeks before Kennedy’s assassination. Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson decided that the instability in South Vietnam needed to be regulated, especially after a 1964 attack against American soldiers in The Gulf of Tonkin. By 1965, with Congress granting Johnson unprecedented power to wage war, some 82,000 combat troops were stationed in Vietnam, and military leaders were calling for 175,000 more by the end of 1965 to shore up the struggling South Vietnamese army and from 1964-1973, the United States covertly dropped two million tons of bombs on neighboring, neutral Laos during the CIA-led “Secret War” in Laos. The bombing campaign was meant to disrupt the flow of supplies across the Ho Chi Minh trail into Vietnam and to prevent the rise of the Pathet Lao, or Lao communist forces.

The Draft

In the United States, military conscription, commonly known as the draft, has been employed by the U.S. federal government in six conflicts: the American Revolutionary War, the American Civil War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.

The draft, as we know it, came into being in 1940 with the Selective Training and Service Act. This Act required that men who had reached their 21st birthday but had not yet reached their 36th birthday register with local draft boards. Later, when the U.S. entered World War II, all men from their 18th birthday until the day before their 45th birthday were made subject to military service, and all men from their 18th birthday until the day before their 65th birthday were required to register.

During the Vietnam War era, between 1964 and 1973, the U.S. military drafted 2.2 million American men out of an eligible pool of 27 million. Although only 25% of the military force in the combat zones were draftees, the system of conscription caused many young American men to volunteer for the armed forces in order to have more of a choice of which division in the military they would serve.

Most of U.S. soldiers drafted during the Vietnam War were men from poor and working-class families. These were young men who were not going get a college deferment, have a political connection, or have a family doctor that could give them a medical deferment. American forces in Vietnam were 55% working-class, 25% percent poor, 20% middle-class. Many soldiers came from urban areas or farming communities.

In order to address this inequity, a lottery system was put into place. The draft lottery was based on birth dates. There were 366 blue plastic capsules containing birth dates (including February 29) placed into a glass container. The capsules were drawn by hand, opened one by one, and then assigned to a sequence from 1 until 366. The first date drawn was September 14, followed by April 24, which was assigned to “001” and “002” respectively. The process continued until each day of the year was assigned to a lottery number. Eventually all men with number 195 or lower were called in order to report for physical examinations in 1970.

Aftermath & Legacy

After he was inaugurated, Nixon believed that the “Silent Majority” actually supported the war effort and decided that rather than a full withdrawal of troops, he would launch the “Vietnamization” process — a system by which he could train, equip and fund the Vietnamese soldiers into self sufficiency. At home, desertion rates quadrupled from 1966 levels. Among the enlisted, only 2.5% chose infantry combat positions in 1969–1970. ROTC enrollment decreased from 191,749 in 1966 to 72,459 by 1971, and reached an all-time low of 33,220 in 1974, depriving U.S. forces of much-needed military leadership.

1971 alo brought a new blow to American war support. A top-secret Department of Defense study of U.S. political and military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967 was published in the New York Times in 1971—shedding light on how the Nixon administration ramped up conflict in Vietnam. The report, leaked to the Times by military analyst Daniel Ellsberg, further eroded support for keeping U.S. forces in Vietnam.

In January 1973, the United States and North Vietnam concluded a final peace agreement, ending open hostilities between the two nations. War between North and South Vietnam continued, however, until April 30, 1975, when DRV forces captured Saigon, renaming it Ho Chi Minh City (Ho himself died in 1969). The two states were unified in 1976 and became the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

In terms of the U.S. involvement in the conflict, it turns out that even the leaders of the war effort would come to side with the general public and protesters. Christian G. Appy writes for The New York Times:

Three decades later, Robert McNamara, a key architect of the Vietnam War who served as defense secretary for both Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, renounced those wartime claims — the very ones he and others had invoked to justify the war. In two books, “In Retrospect” (1995) and “Argument Without End” (2000), McNamara conceded that the United States had been “terribly wrong” to intervene in Vietnam. He attributed the failure to a lack of knowledge and judgment. If only he had understood the fervor of Vietnamese nationalism, he wrote, if only he had known that Hanoi was not the pawn of Beijing or Moscow, if only he had realized that the domino theory was wrong, he might have persuaded his presidential bosses to withdraw from Vietnam. Millions of lives would have been saved. If only.

The Vietnam Conflict Extract Data File of the Defense Casualty Analysis System (DCAS) Extract Files contains records of 58,220 U.S. military fatal casualties of the Vietnam War. In 1995 Vietnam released its official estimate of the number of people killed during the Vietnam War: as many as 2,000,000 civilians on both sides and some 1,100,000 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong fighters. The U.S. military has estimated that between 200,000 and 250,000 South Vietnamese soldiers died. Among other countries that fought for South Vietnam, South Korea had more than 4,000 dead, Thailand about 350, Australia more than 500, and New Zealand some three dozen.

In the end, the United States spent more than $120 billion on the conflict in Vietnam from 1965-73; this massive spending led to widespread inflation, exacerbated by a worldwide oil crisis in 1973 and skyrocketing fuel prices.

Preview Image Details

(information about the image that accompanies links to this page)

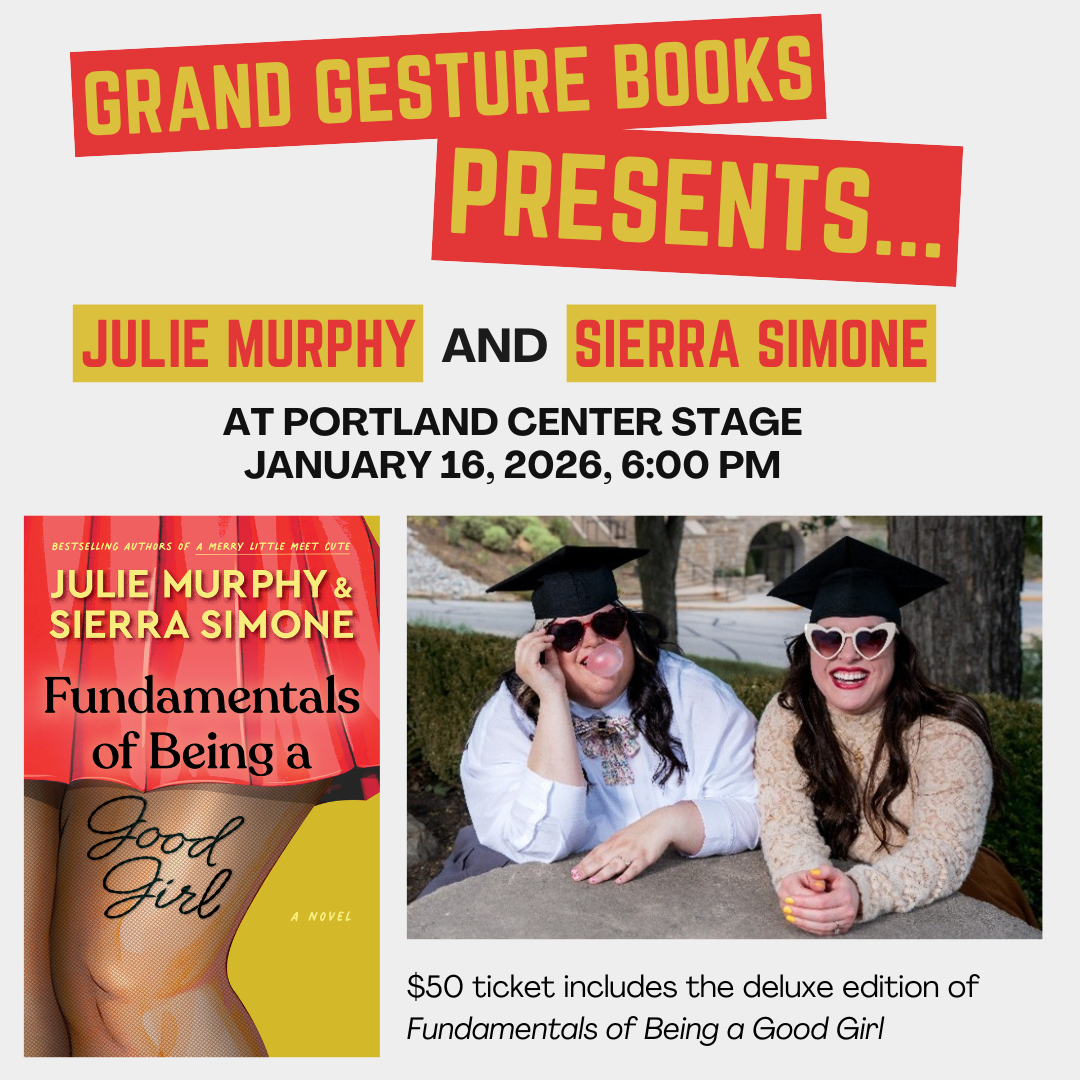

Scenic backdrop rendering by Diggle

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).