The Songs That Held Us Up

In 1619, when the first ships carrying enslaved Africans reached America, they brought with them a wealth of cultures, traditions, and heritages. Over the course of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, some 12.5 million people were stolen from Africa. What was able to miraculously emerge from these unthinkable circumstances was a unique culture that shaped the country and the world in indelible ways. A piece of this culture that cannot be separated from the sorrow and brutality, but also the hope and resilience, is the creation of musical traditions which have survived the centuries. The music in Choir Boy, which could be categorized as Negro spirituals and folk songs, marries enduring legacies and living history, passed through the oral tradition of Africans in America. The power of this legacy cannot be overstated. As Choir Boy playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney said in an NPR interview in 2019, “These are the songs that have held us up.”

These songs, constructed of both African and European elements, are considered to be the first musical form created by non-Indigenous peoples in America. Much of the lyrical content in Negro spirituals is Christian in its nature, and in fact, many of the songs are reworked from those which white enslavers sang in their own church services. As early as 1787, however, Black Christians had established their own congregations that always gathered alone secretly to worship and practice their religious customs. Because Africans were forbidden to learn to read and write, a cornerstone of this practice rested in the spoken and sung word. It is important to note that while some enslaved folks embraced Christian doctrine, many outright rejected it and some songs had lyrics that rang out “I don’t wanna ride no golden chariot, I don’t want no golden crown.” Still, the Black church was and remains an important cultural center. And this music born from religious experience honors, as historian Kaitlin Greenidge wrote, “the consciousness of the enslaved and thus continue[s] the resistance to the enslaver’s definition of reality.”

A feature prominent in Negro spirituals and folk songs, which are often performed a capella, is call-and-response. A lead singer begins a line and the larger choral group answers back. This is illustrated in the song “I Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray” where the soloist calls out various locations, such as “in the valley” or “chilly waters,” and the chorus responds “I couldn’t hear nobody pray.” In certain traditional African American Churches, another form of call-and-response still exists. This form, called Lining a Hymn, requires someone to speak the words of the song line by line, pausing for the congregation to respond by singing the lines.

The songs sung by enslaved people, while often spiritual or religious in nature, were not simply a form of worship. Many believe these songs to be practical as well. Abolitionist Frederick Douglass acknowledged that mentions of “Canaan Land” often referred to Canada. It is believed that some songs held codes for escape and freedom. Whether this is true or not, it is obvious that African American folk songs served layered purposes. “Wade in the Water” may have given instructions; “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” may have offered the hope of heaven; and “Go Down Moses” may have expressed protest — likening the enslaved Africans with the enslaved Israelites in Egypt. But the immediate and perhaps chief purpose of this music was to crystalize the experience of living in bondage. In his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Douglass wrote:

[Enslaved people] would make the dense old woods, for miles around, reverberate with their wild songs, revealing at once the highest joy and the deepest sadness. They would compose and sing as they went along, consulting neither time nor tune. The thought that came up, came out — if not in the word, in the sound — and as frequently in the one as in the other. … Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.

This music, like perhaps all music, existed to illustrate the interior lives of those singing it. It could have been coded, but it also may have been simply the only way one could have to express oneself. After emancipation, this music did not die, though many believed it should. In 1871, students from Fisk University, a historically Black college in Nashville, Tennessee, formed the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Originally formed as a fund-raising effort for the school, they became instrumental in bringing the secret and sacred songs of the formerly enslaved to the white mainstream. Even original members of this group resisted sharing what they called “slave songs.” One member, Ella Sheppard, noted, “They were associated with slavery and the dark past and represented things to be forgotten.” But eventually, she and the other Jubilee singers “began to appreciate the wonderful beauty and power of our songs.” Historians credit Fisk’s world tour with introducing Negro spirituals, which until then had only been sung in closed company, to performance stages.

The beauty and power of this music continued to endure. It is no wonder these songs, which were salve and defiance in one generation, became the soundtrack of many liberation movements of the 20th century. Labor advocates in the 30s and 40s sang “I Shall Not Be Moved,” a song dating back to the 19th century. The Civil Rights Movement of the 50s and 60s was underscored by the songs created by the first Africans on this continent. Similar to the originals, the lyrics were refashioned to suit the needs and sentiments of the people singing them. The song “Keep Your Eye on the Prize,” which was often sung at protests and marches, was originally sung “keep your hand on the plow.” While both iterations encourage perseverance and can be interpreted to mean keep your focus on the eternal goal of heaven and salvation, each also holds the subtext of a call to fight for freedom. The refrain in both remains “hold on.” This particular spiritual is considered the unofficial anthem of the Civil Rights Movement and has been recorded by countless artists, from Mahalia Jackson to Bruce Springsteen. Today, songs like “Hell You Talmbout” by Janelle Monae and “Glory” by John Legend and Common borrow themes and melodies from Negro folk songs.

The legacy of Negro spirituals and folk songs can be felt in nearly every aspect of American popular music. Jazz, blues, some country, rock ‘n’ roll, R&B, and hip-hop can all be traced back to these songs passed down through generations. The DNA of American musical history is stamped with the heart and soul of Black folk. Choir Boy stands solidly in the tradition from which it comes, leaning on the same principles and purposes of the origins of this art form. Like the Fisk Jubilee Singers, who are still active to this day, the men of Charles R. Drew Prep have committed to being a link in the chain of our living history, which survives chiefly by word of mouth.

Spirituals, Folk Songs, and Work Songs

While often thought of interchangeably due to sharing many characteristics, there are slight shades of difference between folk songs, work songs, and Negro spirituals — all of which appear in Choir Boy. They are all birthed and created in the same or similar conditions and survive mainly through the oral tradition.

Folk Songs

- Traditional folk music has been defined in several ways: as music transmitted orally, music with unknown composers, music that is played on traditional instruments, music about cultural or national identity, music that changes between generations (folk process), music associated with a people's folklore, or music performed by custom over a long period of time.

Work Songs

- A piece of music closely connected to a form of work, either sung while conducting a task (usually to coordinate timing) or a song linked to a task which might be a connected narrative, description, or protest song.

Spirituals

- Religious songs of a kind associated with Black Christians of the southern US and thought to derive from the combination of European hymns and African musical elements by enslaved Black people.

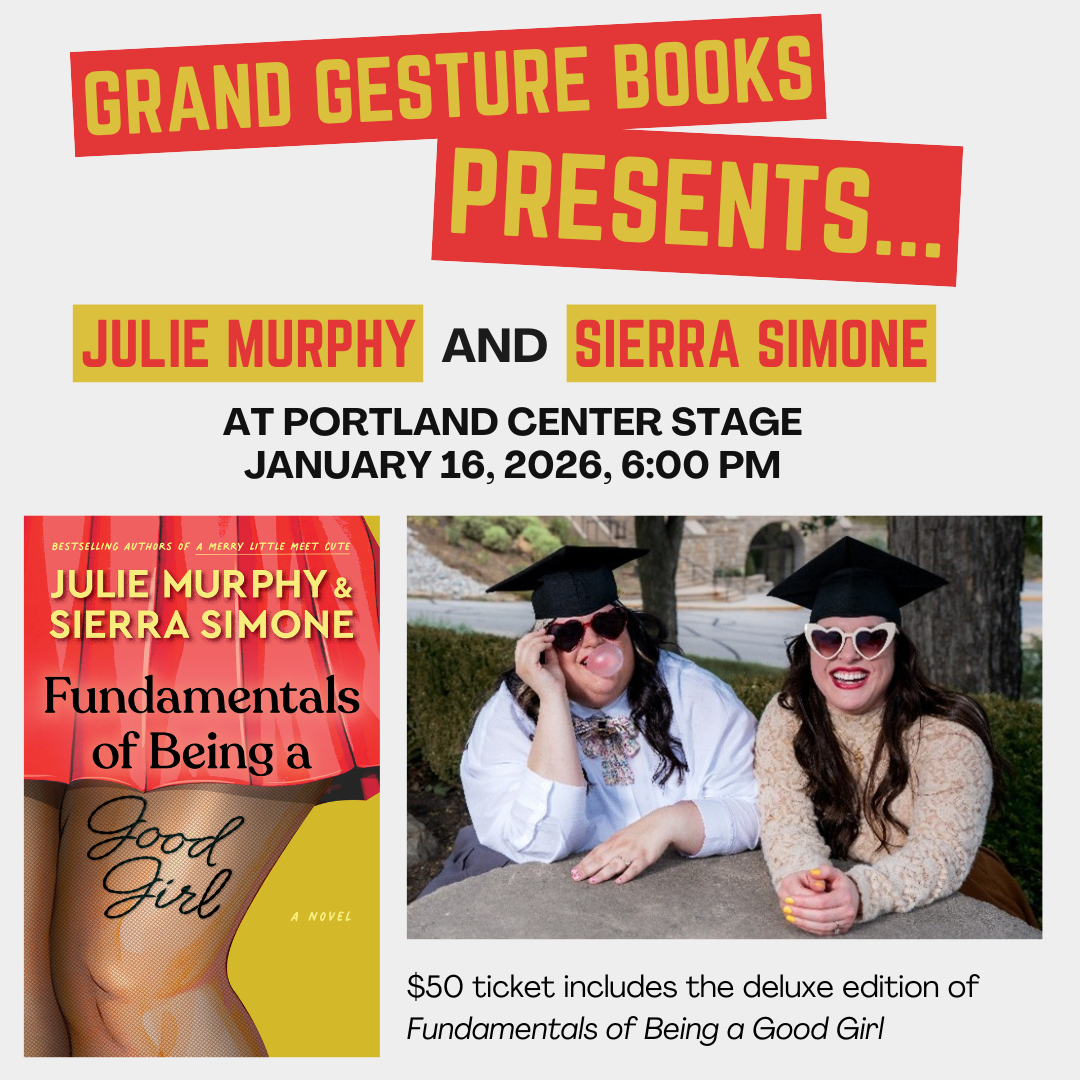

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).