Shakespeare's England

England

In 1600, the population of London was 245,000 people – double the size of Paris and Amsterdam, making the city, and therefore England, a central force in European and world culture. London became a booming trade station handling 85 percent of all exports. Wool textiles gained popularity as their quality and craftsmanship became known. Many people realized this, and as a result ranchers, laborers, merchants, and clerks throughout England profited, receiving healthy wages and incomes. Shakespeare’s London was home to a cross-section of early modern English culture. Its populace of roughly 100,000 people included royalty, nobility, merchants, artisans, laborers, actors, beggars, thieves, and spies, as well as refugees from political and religious persecution on the continent.

Alongside all of this growing prosperity, however, lived a growing mortality. People in Shakespeare’s time rarely lived past the age of 30 and nearly one half of all the children born never lived beyond 15 years old. This is in large part due to the lack of medical knowledge, the rampant spread of disease and an uncertain food supply. The plague and other diseases left Englanders so vulnerable that often the theaters were closed, for fear that the close contact of the audience members could bolster the contagion.

As the cities grew, and the rich got richer, poverty rates also saw a rise. Those in the middle saw the ability to rise to the top but those on the bottom often suffered. The growing numbers of the poor led to charity from the Church, and welfare legislation. While the government saw the need to help enough for the poor to not be left to starve, that was virtually the extent of its aid. In fact, many of the laws passed to help the poor, were done so begrudgingly and created a system of beggar’s licenses, which limited where the poor could go, and how long they could beg. These licenses were notoriously difficult to obtain, and therefore many of them were forged.

England stayed in a religious and political flux for much of the period. Beginning with the split from the Roman Catholic Church, and the establishment of the monarch as both the head of the Church and the supreme political leader – the years between Henry VIII’s rule and the beginning of James I’s kingship, England had been through several religious movements. The Elizabethan Era saw a continued fight between the increasingly persecuted Catholics, the growing Puritan power and the Church of England. Queen Elizabeth’s reinstatement of the English Book of Common Prayer’s in 1559, however, allowed more of the illiterate English common folk to attend an English language mass. Queen Elizabeth believed herself to govern “with the consent of the people '' but also believed that she was ordained by God to lead the country.

The Crown was quite involved in the everyday lives of the citizens of England – so much so that laws even dictated what one might wear. The Statutes of Apparel were passed in 1574 and they dictated, depending on one’s social standing, what fabrics one could wear, which colors and styles one could wear and even how much one could spend on clothing a year.

Queen Elizabeth I

Born September 7, 1533, the girl who would come to be known as Gloriana, The Virgin Queen, or Good Queen Bess, was the child of Henry VIII and his second wife Anne Boleyn. Henry’s marriage to Anne caused major political waves, as to marry her he had to break with the Catholic church and divorce his first wife Catherine of Aragon. He wished to have a male heir as Catherine had only birthed a daughter, Mary. When Elizabeth was not yet three years old, Henry VIII had Anne Boleyn beheaded and their marriage delegitimized – therefore making Elizabeth illegitimate. Henry’s third wife, Jane Seymour, gave him a son, Edward – a legitimate, and male, heir to the throne.

Though considered a bastard child in the eyes of the Church, and the law, Elizabeth was treated the same as the other children by her father. She was rigorously educated and well kept. Henry presented her as the third in line for the throne, behind her half siblings Edward and Mary. When her father died in 1547, Edward ascended the throne at just 9 years old. His was a Protestant government, broken with the Catholic Church. His reign lasted only 6 years. When the young king was 15, he fell terminally ill and knowing he would die, drew up succession papers which named his cousin Lady Jane Grey as heir. Jane ruled for just nine days, as Mary deposed her and took up the throne.

Mary’s similarly short reign was nonetheless quite impactful on England. She rejected her father and brother’s Protestantism and re-established ties with the Roman Catholic Church. Dubbed “Bloody Mary” by her opponents, she had over 280 Protestants executed during her 5-year tenure as queen. Mary died of cancer in 1558 and having no heir, the throne then fell to Elizabeth.

Crowned on November 17, 1558, Elizabeth I became one of England’s most successful monarchs. She is credited with the firm establishment of the Church of England, breaking completely and finally from the Roman Catholic Church. England's defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 associated Elizabeth with one of the greatest military victories in English history. During her 45 years as regent, England saw its longest lasting peace time in recent memory, the further exploration of the Americas, an artistic and cultural renaissance and the establishment of England as a political, economic and military giant. Though she had many opponents, namely The Catholic Church and who they would see as queen – Mary, Queen of Scots – her moderate ideals and tolerance for freedom of religion also made her quite popular.

In addition, she was of a singular personality. Considered strikingly beautiful, with fiery red hair and a made-up face, an incorrigible flirt, an unrivaled wit and intelligence, Elizabeth I was the center of a great cult of followers and supporters. Though she died unmarried, and reportedly virginal, leaving behind no heir – Elizabeth I’s reign as Queen of England remains one of the most impactful and successful. She is one of the few monarchs, and indeed people, to have a period of history named singularly after her.

Queen Elizabeth died at the age of 69, likely of blood poisoning from the lead in her cosmetics, which she wore until her death. She was succeeded by James I, son of Mary, Queen of Scots. James inherited the “Golden Age” Elizabeth had ushered in. Elizabeth was five years into her rule as queen when William Shakespeare was born in 1564. Though she only saw a few of his plays, Elizabeth expressed fondness for many of Shakespeare’s earliest works. Legend has it that she so enjoyed the character, Sir John Falstaff, from Henry IV Part I, that she insisted that Shakespeare write a play focused on him. That play would become the comedy, The Merry Wives of Windsor. In 1601, Elizabeth commissioned Shakespeare to write a play to be part of her Christmas Festivities, the last night of these occurring on Twelfth Night.

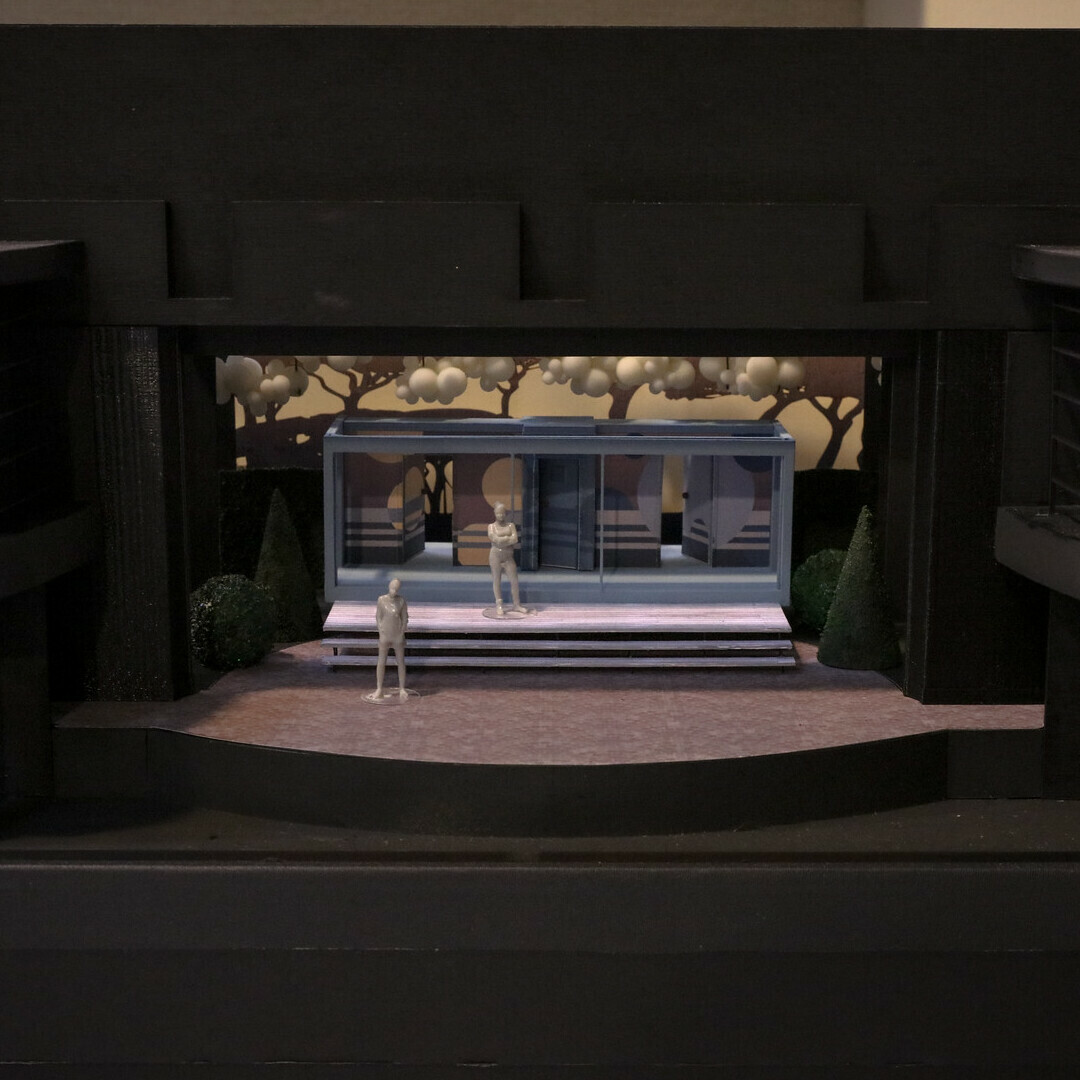

Stage Conventions

The typical Elizabethan stage was a platform as large as 40 square feet, sticking out into the middle of the yard so that the spectators nearly surrounded it. Performers worked exclusively in repertory, sometimes rehearsing and performing upwards of 20 plays a year and covering multiple roles in each show. Because of this and because of laws about clothing, many costumes were brightly and distinctly colored. This allowed characters to be easily recognized, not only for the part they played in the plot, but for their social standing, gender and identity. Elaborate

costuming was also a supplement for the sparse scenic and lighting elements.

Theatergoing in Shakespeare’s time was a polarizing event. On one hand, those of the extreme religious sects believed theater making and therefore the attendance of plays to be sinful. On the other hand, it is believed that 1 in 8 Londoners regularly attended the theater, with about 15,000 people seeing plays weekly. And though Queen Elizabeth enjoyed plays, and often had them performed for her at court, there were lots of laws which dictated what and who could appear on stage.

It is well known that women were not allowed to appear on stage and that all parts were performed by men or young boys as female parts. Many writers, including Shakespeare, often wrote dialogue which reminded the audiences that they were seeing a female character to avoid confusion.

In May 1606, a statute was passed “for the preventing and avoyding (sic) of the great Abuse of the Holy name of God in Stageplayes, Interludes, Maygames, Shewes, and such like”. Noncompliance resulted in a £10 fine for each offense. It is believed by some scholars that in the original Twelfth Night production, which predates this law by a few years, used God instead of the many instances Jove appears, and that later it was rewritten, either by Shakespeare or someone else to appear in accordance with the law.

Anti-Theatrical Sentiments

There has been anti-theatrical sentiments for the entirety of the art’s existence. Plato even opposed theater, on the grounds that it was all an elaborate lie, and thus philosophically undesirable. As Christianity took hold in the world, religious leaders adopted Plato’s argument for moral reasons. Actors, first, were lying by pretending to be that which they were not, and, second, since actors were required to commit evil acts on stage, this sin was doubly compounded. Theater was virtually eradicated as Rome declined and the Church took root, but reemerged in the Middle Ages as a way to teach Bible lessons to the largely illiterate masses. Opposition to these Medieval plays cited not only that theater was a lie, but that it induced too much pleasure in the viewer, and therefore was sinful.

As the Protestant Reformation began, emerging religious leaders opposed not only traditional playacting, but all that could be considered “theatricalized” including rituals in church, the robes worn by ministers, symbolic décor, etc.

Social Hierarchies

English society was organized in five major classes. Nobility rests at the top, followed by the gentry, merchant, the yeomanry and the poor. The church existed outside of this structure, somewhere above the gentry and in some cases alongside the nobility, with a complex structure of its own. Indeed, each of these classes have their own substructures.

One was either born noble, or had it conferred upon oneself by the king or queen. Noblemen were rich and powerful, and were often seen as threatening to the monarch, which is why it was rare to be appointed a nobleman by the queen. Noble titles include, in descending order, King/Queen, Duke/Duchess, Marquess/Marchioness, Earl/Countess, Viscount/Viscountess, and Baron/Baroness. Members of the noble class owned large households and there was a division of the old families, who were typically catholic, and the new families who were more generally protestant.

The Gentry included aristocrats who owned smaller lands and households, but may hold considerable wealth. Knights, squires and gentlemen/gentlewomen were members of this class. Members of this class were generally well educated and wealthy enough to not be required to work with their hands. They could save, and through wealth acquisition or marriage might find themselves elevated to nobility. Gentlemen and women were often, in their youth, placed in service to members of the noble class – employed in such positions as pages, henchmen – even chambermaids. This could be the result of family politics or in the pursuit of education – and so it was possible to be both servant and gentleman at the same time.

The merchant class was occupied by tradesmen, shopkeepers and innkeepers. The members of this class provided goods and services for others. Amongst the yeomanry were the “middle class” of society. They worked for their income and may own very little land, but lived off this land. In the middle gray space between the yeomanry and the poor was the servant class. Lowborn servants enjoyed the “protection” of a house – be it either the house of gentlemen or nobles – without the wealth and income of the upper classes. The poor followed lastly and were beggars and low laborers.

While modern audiences may have a more rigid sense of the social structure of the Elizabethan era, it is more likely that it was more movable than we believe. In 1581, Richard Mulcaster wrote “all the people which be in our countrie (sic) be either gentlemen or of the commonality.”

Preview Image Details

(information about the image that accompanies links to this page)

Queen Elizabeth I

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).