Rise of the phone zombies: What we lose when technology gives us everything

Salon's Andrew Leonard spoke with Each and Every Thing playwright and performer Dan Hoyle last fall in San Francisco.

As we walk to a café in the heart of San Francisco’s Mission District, Dan Hoyle tells me that his one-man show, Each and Every Thing, has just been extended for a second time, until Oct. 4. The news confirms what I already suspected: Hoyle is the right man in the right place at the right time. His hilarious, moving and inspirational critique of our smartphone-centric lifestyle feeds a desperate hunger for meaning acutely felt in the exact neighborhood we are strolling through. We love our new technology in the Bay Area, but we’re also getting more than a little alarmed by it. What exactly are we doing to ourselves as we submerge ecstatically into the screen? Is this really how we want to live?

We sit down at a sidewalk table on Valencia Street, a block away from the Marsh theater, where Hoyle has been performing in front of sold-out audiences since June. Next to us, a couple of tech bros are talking about content management systems. Beneath Hoyle’s chair, the word “gentrotech” is stenciled on the sidewalk, embellished with an illustration of curved devil’s horns. It’s not hard to guess that the street art is a product of endangered indigenous inhabitants irate at how rapidly the Mission is changing.

The political and economic transformations precipitated by the latest wave of digital innovation provide the cultural backdrop for Each and Every Thing. But the essence of Hoyle’s show is the search for something more ineffable — real human connection, the kind built from eye contact instead of Facebook likes — in a world in which our behavior in public space is increasingly isolated and isolating. We’ve all seen what Hoyle’s talking about: a couple out for a date both staring down at their phones; pedestrians locked so deeply into Facebook or Twitter that they barely avoid bumping into each other; a subway car in which every single commuter is thumbing his or her way through Instagram or Imgur or Candy Crush. Phone zombies, everywhere, a plague of the digital undead that swept across the world before we fully realized what was happening. (Because we were too busy playing with our amazing smartphones!)

The miracle of Each and Every Thing is that in just 75 minutes onstage, inhabiting a dozen or so characters, from Aryan Brotherhood muscle heads to Chicago drug dealers to Indians sharing coffee and conversation in Calcutta, Dan Hoyle manages to create the very sense of human connection that he yearns for — with his audience. He doesn’t hector, he doesn’t lecture, and except for one very funny moment about two-thirds into the show, he doesn’t get angry (aside from when he’s depicting the aforementioned Aryan). He follows the cardinal rule of great narrative; he shows, he doesn’t tell. And as he shares his own story, the life of a performer whose highest artistic goal is to get to know people on a deep level and share theirstories, he enacts his message.

Each and Every Thing is a true story. The characters Hoyle inhabits are real people that Hoyle has met– including his best friend, an Indian-American software developer. Hoyle uses these characters to illustrate his personal journey to understand himself as an artist, sandwiched around the disruption caused by the smartphone, which inhibits all of us from understanding ourselves and each other.While turning a critical eye on contemporary digital mores, Hoyle makes it clear that we need to find a new balance between our machines and the people around us, and, in the process, he demonstrates just how to adjust the scales. It’s a bravura performance, and so very, very necessary.

* * *

It is an inescapable irony of our contemporary existence that less than 24 hours after I saw Each and Every Thing — a show in which Hoyle not only asks everyone to turn off their phones, but tells us that he hopes we keep them turned off for an hour or two after the show — we’re connecting directly, for the first time, via Facebook. But Hoyle is unbothered by what could be deemed a trifle hypocritical. He loves technology as much as the next 34-year-old raised in San Francisco (and currently living in New York). He’s not opposed to social media, in principle. He owns a smartphone.

But he’s convinced that the emergence of that smartphone as our default interface with basically everything has altered something significant about how we behave when in public.

“It’s one thing when we’re all alone in our homes, connecting online,” says Hoyle. “But when we’re out in public checking in on our phones, we are creating new private spaces in the public arena.”

“Something has changed. You have five minutes to kill, and instead of looking around, maybe having some random conversation with a stranger, maybe just sharing some glances … we’re looking at our phones. I think these new technologies enable a level of self-isolation that’s greater than ever before.”

It all makes sense, says Hoyle, quoting a line from his show, because “reality is awkward … And life through a screen is less awkward.”

Anyone with a bare minimum of self-awareness can appreciate Hoyle’s critique. I tell him that ever since I’ve owned a smartphone, I’ve stopped reading magazines off the rack at the local grocery store, but I’ve also started feeling increasingly guilty about that behavioral modification. Not just because the collective impact of people like me on off-the-rack magazine sales has been devastating, but because I wonder how alienating it must be for the cashier to see a long line of people staring down at their phones, only raising their eyes when it is time to pay. And yet, on those rare and horrible occasions when I forget to bring my phone with me, I feel destitute, at the mercy of an unforgiving universe.

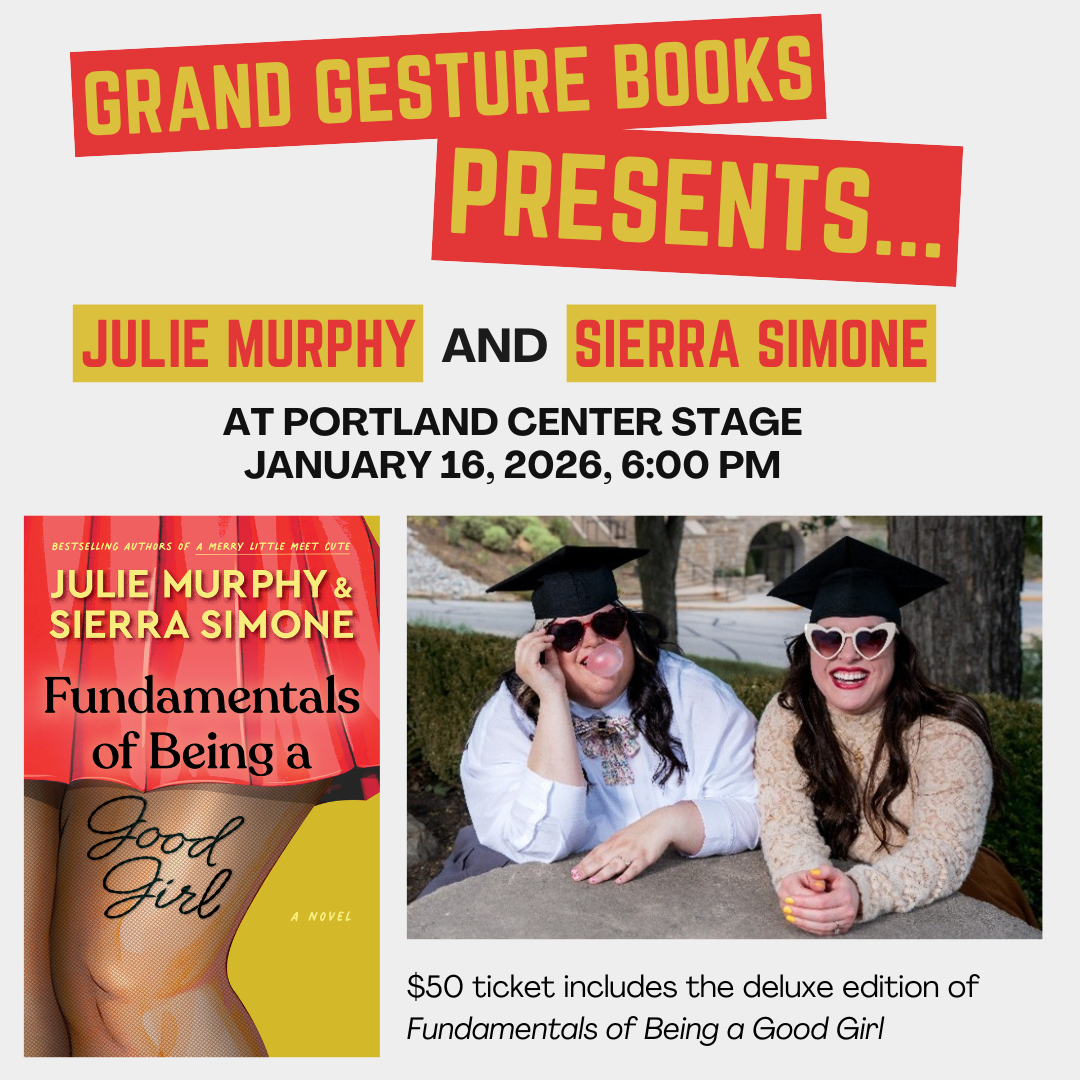

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).