Resource Guide for Mary's Wedding: Literary Influences in the Play

"Before 1914, poems of war had been few and idyllic. Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Charge of the Light Brigade, which is quoted in the play is one well known example. The poem describes the courage of the British cavalrymen involved in a charge in October of 1854, during the Crimean War, a war between England and Russia. This dramatic poem venerates the “six hundred” British soldiers, and romanticizes the battle. It’s portrayal of war encouraged the character, Charlie, and young men like him to enlist in the Great War. However, there is much to take into consideration while reading Charge of the Light Brigade.

Tennyson was a descendant of England’s King Edward III and attended at Trinity College in Cambridge. In 1850 he was appointed England’s poet laureate. A poet laureate is officially appointed by a government and expected to compose poems for state occasions and in support of government actions. The Charge of the Light Brigade was just such a poem. Poems like this were a form of propaganda. Tennyson supposedly wrote the poem after reading an account of the battle in The Times. Tennyson himself never fought in a war. The poem became very popular, and remained a classic piece of English literature. By the turn of the century, when Charlie and Mary were in school, it was easy to forget that the real Charge of Light Brigade had been a disaster in which 118 British soldiers were killed.

Tennyson wrote in his poem that for the soldiers of the Light Brigade “Theirs not to reason why,/Theirs but to do & die.” Such blind obedience might be considered patriotic and heroic in time of war, however, this “do and die” attitude can also be the mark of people who are not educated enough to voice a dissenting opinion. The common cavalryman of the Light Brigade did not leave a record of his feelings about war. However, by 1914 the combination of compulsory schooling and cheap printing (both developments of the late 19th century) greatly increased the literacy rate around the world. In a war with long, uneventful periods of entrenchment, thousands of educated soldiers took up their pens.

Many soldiers used their spare time in the trenches to write poems or make sketches. A huge number wrote long letters home or kept a diary. They expressed a vast range of opinions and beliefs about the war. Some soldiers were even more xenophobic and nationalistic than any propaganda back home. Many thought that the war would end very quickly. Some were opposed to the war. As the war dragged on and became more deadly and horrifying, these critical voices became increasingly vocal in their disapproval. One dissenter was Wilfred Owen, a British soldier who wrote graphic poetry about the horrors of trench and gas warfare. Two of his most famous poems are Dulce Et Decorum Est and Anthem for Doomed Youth. Owen’s greatest influence was his friend and fellow soldier-poet Siegfried Loraine Sassoon. Sassoon’s realistic poem Counter-Attack ends with the explicit statement “the counter-attack had failed”, making it a perfect foil to the Charge of the Light Brigade, where loss was not acknowledged."

The Charge Of The Light Brigade

by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Half a league half a league, Half a league onward, All in the valley of Death Rode the six hundred: ‘Forward, the Light Brigade! Charge for the guns’ he said: Into the valley of Death Rode the six hundred.

‘Forward, the Light Brigade!’ Was there a man dismay’d ? Not tho’ the soldier knew Some one had blunder’d: Theirs not to make reply, Theirs not to reason why, Theirs but to do & die, Into the valley of Death Rode the six hundred.

Cannon to right of them, Cannon to left of them, Cannon in front of them Volley’d & thunder’d; Storm’d at with shot and shell, Boldly they rode and well, Into the jaws of Death, Into the mouth of Hell Rode the six hundred.

Flash’d all their sabres bare, Flash’d as they turn’d in air Sabring the gunners there, Charging an army while All the world wonder’d: Plunged in the battery-smoke Right thro’ the line they broke; Cossack & Russian Reel’d from the sabre-stroke,Shatter’d & sunder’d. Then they rode back, but not Not the six hundred.

Cannon to right of them, Cannon to left of them, Cannon behind them Volley’d and thunder’d; Storm’d at with shot and shell, While horse & hero fell, They that had fought so well Came thro’ the jaws of Death, Back from the mouth of Hell, All that was left of them, Left of six hundred.

When can their glory fade? O the wild charge they made! All the world wonder’d. Honour the charge they made! Honour the Light Brigade, Noble six hundred!

War Cemetery, Belgian village Woesten

Anthem for Doomed Youth

(1917) by Wilfred Owen

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries for them from prayers or bells,

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,—

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of good-byes.

The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of silent maids,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

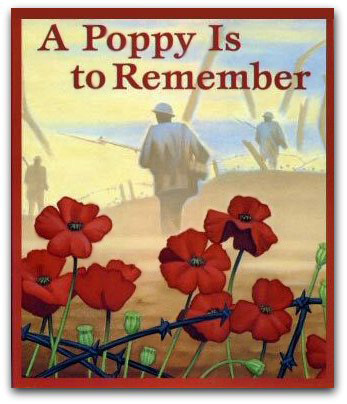

"Perhaps the most famous poem to result from World War I is In Flanders Fields by Canadian army physician John McCrae. His inspiration was the death of a fellow officer, Lt Alexis Helmer, during the Second Battle of Ypres in western Belgium, for whom McCrae had performed the burial service. McCrae’s verses, which he had scribbled in pencil, were sent anonymously by a fellow officer to the English magazine, Punch, which published them under the title ‘In Flanders Fields’ on 8 December 1915. This short poem, spoken from the view of the war dead, is at once both patriotic and tragic. Since the poem encourages the living to “take up our quarrel with the foe” it elicited responses, including In Flanders Now and We Shall Keep the Faith. The poem has reached a mythic status in Canada, with a portion of it printed on the Canadian ten dollar note. Also, poppies are now an international symbol of remembrance.

Edna Jaques was born in Ontario, Canada. In her early twenties, in Calgary, she wrote the following war poem which was to bring her widespread recognition. Later, printed on a card, the poem was sold throughout the United States at ten cents a copy and raised one million dollars for war relief. It was later read at the unveiling of the tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Washington, D.C. Unfortunately, her vision of peace would not prevail.

In Flanders Now

By Edna Jaques

We have kept faith, ye Flanders' dead,

Sleep well beneath those poppies red,

That mark your place.

The torch your dying hands did throw,

We've held it high before the foe,

And answered bitter blow for blow,

In Flanders' fields.

And where your heroes' blood was spilled,

The guns are now forever stilled,

And silent grown.

There is no moaning of the slain,

There is no cry of tortured pain,

And blood will never flow again

In Flanders' fields.

Forever holy in our sight

Shall be those crosses gleaming white,

That guard your sleep.

Rest you in peace, the task is done,

The fight you left us we have won.

And "Peace on Earth" has just begun

In Flanders now.

Moina Belle Michael was born in Georgia in 1869. Her father was a Confederate veteran of the Civil War. The idea for the Flanders Fields Memorial Poppy came to Moina Michael while she was working at the YMCA Overseas War Secretaries’ headquarters at Columbia University on a Saturday morning in 1918, two days before the Armistice was declared. In a magazine she came across a vivid color illustration for the poem “We Shall Not Sleep” (later named “In Flanders Fields”) by John McCrae. At that moment Moina Michael made a personal pledge to ‘keep the faith’ and vowed always to wear a red poppy as a sign of remembrance and as an emblem for “keeping the faith with all who died.” Compelled to make a note of this pledge, she hastily scribbled down a response on the back of a used envelope, entitled “We Shall Keep the Faith.” She went to a New York department store and purchased 25 artificial red poppies and, pinning one on her own collar, distributed the remainder to the YMCA secretaries with an explanation of her motivation. Moina Michael hereafter tirelessly campaigned to get the poppy adopted as a national symbol of remembrance. In September 1920 the American Legion adopted the Poppy, and the symbol spread worldwide."

In Flanders Field

by John McCrae

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow in Flanders fields.

The Lady of Shalott (1832)

BY ALFRED, LORD TENNYSON

Part IV

In the stormy east-wind straining,

The pale yellow woods were waning,

The broad stream in his banks complaining,

Heavily the low sky raining

Over tower'd Camelot;

Outside the isle a shallow boat

Beneath a willow lay afloat,

Below the carven stern she wrote,

The Lady of Shalott.

'The Lady of Shalott is an 1888 painting by the English Pre-Raphaelite painter John William Waterhouse.

Use the code MWGUIDE for 100 points on PlayMaker! Visit www.pcsplaymaker.com for more info.

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).