Resource Guide for Educators: The History of the Game

The Oregon Trail Game:

The Oregon Trail has the distinction of being the longest-published, most successful educational game (65 million copies sold) of all time. Three student teachers, Don Rawitsch, Bill Heinemann, and Paul Dillenberger, created The Oregon Trail in 1971 to help Minnesota schoolchildren learn American History. First programmed on a primitive teletype printer, the game challenged students to assume the role of Western settlers crossing the continent on the way to the Pacific coast. Players had to choose which items to bring, how fast to travel, and what to do when food ran low or disease struck. In 1974, Rawitsch joined the Minnesota Educational Computer Consortium (MECC). The MECC was looking for ideas for an emerging business of educational games for schools and Rawitsch offered the code for The Oregon Trail. First released only to schools in Minnesota, MECC improved the initial game before a nationwide release to schools and homes in 1985 with the advent of the Apple II computer.

In 2015, The Oregon Trail was inducted into the Video Game Hall of Fame, sharing the stage with Space Invaders, Grand Theft Auto III, Sonic the Hedgehog, The Legend of Zelda and The Sims.

The Oregon Trail Life Lessons (from the creators)

1) Plan ahead---there's danger out there.

2) Be patient---the journey is long.

3) If you persevere, you will find your green valley.

4) Even if the water is deep, sometimes you just have to caulk the wagon and head out from shore.

Bring Your Machete To Work Day

An essay on what The Oregon Trail game meant for one pre-teen girl

(excerpted from Sloane Crosley’s book I Was Told There’d Be CakeI Was Told There’d Be Cake)

In 1990, after our Apple IIE quit, our family purchased a Macintosh Classic. This was a good thing because the IIE was a constant source of confusion for me. For one thing, it took large flexible disks that were not even, despite all tactile evidence to the contrary, marketed as “floppy disks.” The more current model— disks half their size and so hard you could eat off them— held the public title of “floppy.” (Also neither of these options were, in fact, disc-shaped.) For another, the monitor would freeze or blink incessantly without telling you what was wrong, like a pet or a baby. I tried to fix it myself once and the Brightness knob shot out and hit me in the eye. As if these crimes weren’t enough to make us love the Macintosh Classic by comparison, our new computer came with three free games. One of them was Oregon Trail. I have no idea what the other two were.

A game of moderately tough choices and rawhide, Oregon Trail wound its way through the late 1980s in a very un-’ 80s-like fashion: subtly. Unlike BurgerTime or Tetris, high-speed programs structured around multiple levels, Oregon Trail slowly moved toward a singular goal. It also had a distinct masturbatory quality. Here was something millions of preteens did, only you wouldn’t find out until much later in life. Something one could do over and over again, with no diminishment of rewards. Apparently many children learned how to play it at school, which strikes me as just plain illegal.

For me, Oregon Trail was a private affair— something I engaged in after dinner when I was supposed to be doing homework. At the time I was going through a somewhat awkward phase, both the “somewhat” and the “awkward” being total understatements. I had a chin that jut out when I smiled, as if it were trying to escape from my face. And who could blame it? My eyes were too big for my head, my hair too big for my whole body, and my whole body too flat to be noticed by anyone but me. Sadly, as it is for many of us, my awkward phase found me years before I qualified for a driver’s license or even the alarm code to the house. Homebound and date-free, I enjoyed an early teenagehood of drawing in journals, chatting with inanimate animals, prank-calling boys, and playing Oregon Trail. Oregon Trail, which provided me with the illusion I was actually going somewhere. Once the game began, I became completely enthralled, pausing only to listen for the pattern of stair squeaks that would indicate a parent was descending.

Oregon Trail was built on a completely unmodern premise. This also distinguished it from its contemporaries— there were no robots, no time machines, no spacemen possible in a world where people ate unrefrigerated animal guts and washed their socks in a bucket. Originally designed by a couple of college students to teach kids about the odors and tribulations of pioneer life, the game starts in nineteenth-century Independence, Missouri, and heads toward the west coast. The screen itself— displaying a khaki stretch of land and a mountain range in the distance— never alters. It moves from left to right as your tiny wagon heads west, but there are no pop-ups requiring you to select a weapon, no shifts in perspective, no interiors. It’s like watching some brilliant independent film where there are no cuts and no scene changes, only a wagon and a little thing called destiny. It’s also like watching a lost ant crawl across the kitchen counter.

Though you never see their faces, you can choose your persona— a banker from Boston (likely a metaphor for Reagan), a farmer from Illinois (likely a metaphor for Carter), or a carpenter from Ohio (Jesus?). Each character comes complete with a skill set and a gun (just the one rifle— this was pre-Uzi). For a future vegetarian, I sure shot a lot of venison.

Unlike other games of the day, which had me leaping through traffic or called me “gumshoe,” Oregon Trail left lots of room for creativity. It seemed ripe for the misuse. Like a precursor to the Sims, you were allowed to name your wagoneers and manipulate their destinies. It didn’t take me long to employ my powers for evil. I would load up the wagon with people I loathed, like my math teacher. Then I would intentionally lose the game, starving her or fording a river with her when I knew she was weak. The program would attempt an intervention, informing me that I had enough buffalo carcass for one day. One more lifeless caribou would make the wagon too heavy, endangering the lives of those inside. Really now? Then how about three more? How about four? Nothing could stop this huntress of the diminutive plains. It was time to level the playing field between me and the woman who called my differential equations “nonsensical” in front of fifteen other teenagers. Eventually a message would pop up in the middle of the screen, framed in a neat box: MRS. ROSS HAS DIED OF DYSENTERY. This filled me with glee.

I actually began playing the game in 1990, but it still reminds me of the 1980s. For the sake of this Oregon Trail’s influence, you have to ignore the date discrepancy. There’s always a bit of cultural bleed between decades, and the segue from the ’80s to the ’90s is infamously fluid. Especially if you were still a child in the early ’90s and the formative pop cultural markers of your life were four or five years down the road. It’s the same reason Sunday morning movies can seem unquestionably from the ’80s, but upon closer examination with a digital remote, were made in, like, 1992. Think of slouch socks, of Roxette, of Jennifer Connelly and Elizabeth Shue with full faces. You’re thinking of the ’90s. Much like the Macintosh Classic itself, the ’90s took a while to power up. I find that anything culturally significant that happened before ’93 I associate with the decade before it. In fact, Oregon Trail is one of a handful of signposts that middle school existed at all.

Which brings us to now. Here in the new millennium, there are five versions of the game available, including an Amazon Trail and Africa Trail, but none has provided as much milk to the pop culture teat as the original. Now the wagoneers have realistic movements and facial features. Their adventures have become complicated. But at what cost? Would I be able to go on unceremonious killing sprees now as I did then? Perhaps now you can click a button and see the inside of the wagon, pioneer children napping through a shaky afternoon, dreaming under the dangling hides of eight rabbits and a moose. I know I will continue to wonder. I am too fond of my memories of Oregon Trail and not in the market to have them replaced. Also, I no longer own a machine that plays video games so my curiosity cannot be satisfied without a significant financial commitment. Apparently the game has changed for the better.

It wasn’t long before Oregon Trail was criticized for its complete lack of Native Americans, African Americans, or three-dimensional Americans of any kind. The hunting came under a certain degree of scrutiny as well because apparently guns connote “violence.” Then there was the game’s blatant favoring of rich white males. The banker is by far the best choice for your pixelated proxy. He’s in good health and comes with spare funds, which can be used to buy food in times of famine or the munchies.

Despite this orgy of damning evidence, I still think of Oregon Trail as a great leveler. If, for example, you were a twelve-year-old girl from Westchester with frizzy hair, a bite plate, and no control over your own life, suddenly you could drown whomever you pleased. Say you have shot four bison, eleven rabbits, and Bambi’s mom. Say your wagon weighs 9,783 pounds and this arduous journey has been most arduous. The banker’s sick. The carpenter’s sick. The butcher, the baker, the algebra-maker. Your fellow pioneers are hanging on by a spool of flax. Your whole life is in flux and all you have is this moment. Are you sure you want to forge the river? Yes. Yes, you are.

Crosley, Sloane. I Was Told There'd Be Cake (pp. 56-58). Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

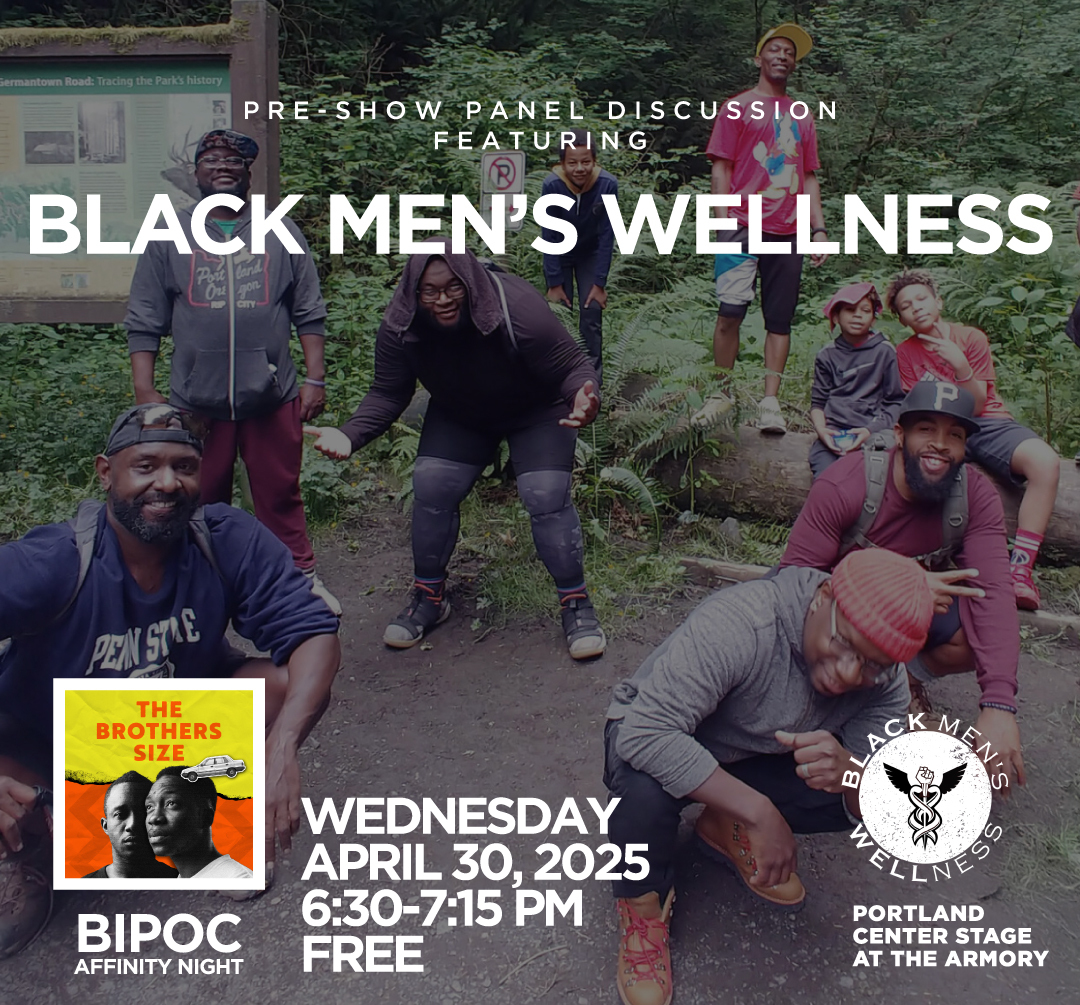

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).