By Bob Greene, CNN Contributor

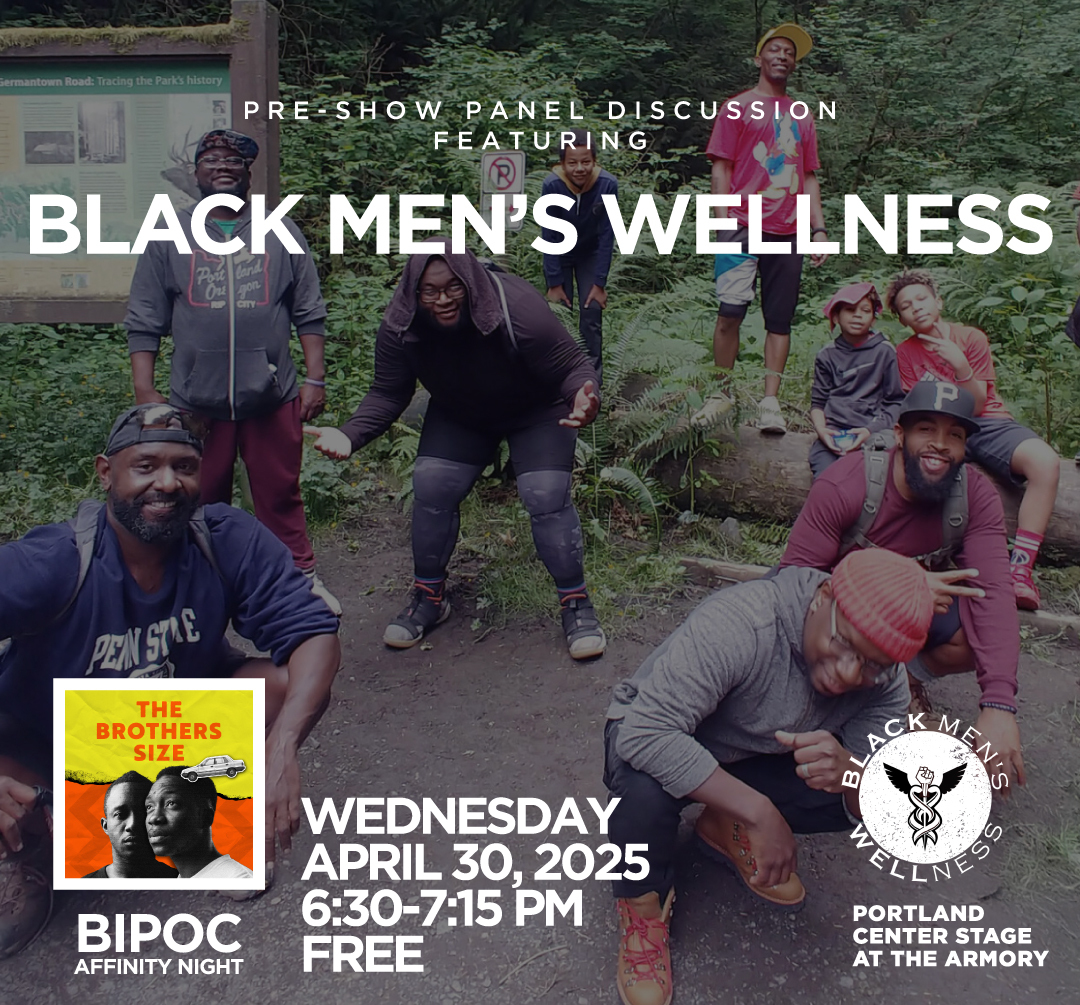

Composer Irving Berlin leads a group of servicemen at Camp Upton on Long Island, New York, in 1942.

Who walks away from $10 million?

Who creates something beloved and beautiful that will eventually earn him well in excess of $10 million, and says he doesn't want the money? The answer is a story of generosity and grace that seems fitting for this season of giving.

I was doing some research on the great songwriter Irving Berlin, who, with his family, fled oppression in Russia when he was 5 years old and came to the United States. He knew no English; he grew up in poverty on New York's Lower East Side. He taught himself music. He wrote the lyrics and melodies to more than 1,500 songs, including some of the most popular in history: "White Christmas," "Easter Parade," "Alexander's Ragtime Band," "This Is the Army, Mr. Jones," "Cheek to Cheek." His feel for the sound of words was close to perfect; if you want to learn the craft of writing, not only music, but any kind of effective writing, study the lyrics -- the precision, the economy, the playfulness, the respect for language and cadence -- of Berlin's "There's No Business Like Show Business." There is not a wasted syllable.

Because "White Christmas" -- the cherished holiday song written by the Jewish immigrant -- will, as usual, be played and sung often this month, I was trying to find out all I could about Berlin's life and career. And came upon an astonishing, profoundly moving act of altruism. It has to do with the song he considered the most important he ever wrote -- the song that meant the most to him.

In 1938, the vocalist Kate Smith was looking for a song to sing on her coast-to-coast CBS radio program to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Armistice Day. She asked Berlin if he would write something for her.

He remembered a song he had begun years before, and had discarded. He brought it out and went back to work on it. Thus it was that, on the CBS radio network one November night, Kate Smith delivered the first public performance of Irving Berlin's "God Bless America." The acclaim was immediate and electrifying. The world was on the verge of a terrible new war; all over the United States, people heard Berlin's song and took it to their hearts. He understood what a valuable property he had on his hands.

And he quietly made a firm decision: He never wanted to make a penny from it. He wanted whatever success the song had to be his gift to the nation he adored. "He believed that the United States had rescued his life," Laurence Bergreen, author of the Berlin biography "As Thousands Cheer," told me. "This was his genuine patriotic gesture. He had a real soft spot for America, and this is how he expressed it."

Berlin instructed attorneys to draw up papers. He wanted to guarantee that every cent "God Bless America" ever earned went to a place that he thought would help to make the country's future brighter and stronger. In those months leading up to the U.S. entry into World War II, he selected the Boy Scouts and the Girl Scouts to receive the song's earnings -- specifically, he wanted the royalties to go to Boy Scout and Girl Scout programs in impoverished and disadvantaged areas.

His binding legal instructions are in effect to this day, 73 years after "God Bless America" was first sung by Kate Smith and 22 years after Berlin's death. So far, there has been more than $10 million distributed to Scouting programs, and it's still coming in. "Irving Berlin and his heirs have never collected a penny," said Bert Fink, an executive in the office that administers the earnings from Berlin's songs.

"He was always a staunch protector of his copyrights," said musicologist Sheryl Kaskowitz, who wrote her Harvard University Ph.D. dissertation on the song, and who is working on a book about it for Oxford University Press. "For him to do this with 'God Bless America' was his sincere thank you to the country." Trustees of the fund Berlin set up are free to allocate the money to programs where they feel it will be beneficial. It has gone to different Scouting organizations over the years. The current recipients of the royalties are the Greater New York Councils of the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts. Officials for both groups told me it is impossible to overestimate how much good the "God Bless America" royalties continue to do for boys and girls with few advantages or resources; there are Scouting programs in homeless shelters and public housing projects that would not exist were it not for the fund.

The popularity of the song has seen ebbs and flows over the years. The country seems to find it anew when it is needed. On September 11, 2001, after the attacks, members of Congress stood together, Republicans and Democrats shoulder-to-shoulder, on the steps of the Capitol and, seemingly spontaneously, joined in singing "God Bless America." That signaled a renaissance for the song; it is now regularly heard at sporting events and public gatherings.

In the final years of Berlin's life, he grew reclusive. He had not had a hit song in decades. Rock music and performances by singer-songwriters had replaced the kind of music he had mastered. But even toward the end, he found comfort in knowing how many young people the royalties from "God Bless America" were helping. His belief was simple: Everyone, regardless of background or beginnings, should be given a chance to shine. After all, look what happened to him.

He died in 1989. The money will continue to go to Scout organizations as long as "God Bless America" is sung and played -- which is to say, as long as there is a United States of America.

Who walks away from $10 million? Irving Berlin did. Happily and proudly. Why? The answer is as clear and direct as the second line in that song of his: ". . .land that I love. . . ."