The New York Times Remembers Gordon Hirabayashi

"Gordon Hirabayashi, World War II Internment Opponent, Dies at 93" by New York Times writer Richard Goldstein, January 3, 2012

Gordon Hirabayashi, who was imprisoned for defying the federal government’s internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II but was vindicated four decades later when his conviction was overturned, died on Monday in Edmonton, Alberta. He was 93.

He had Alzheimer’s disease, his son, Jay, said.

When Mr. Hirabayashi challenged the wartime removal of more than 100,000 Japanese-Americans and Japanese immigrants from the West Coast to inland detention centers, he became a central figure in a controversy that resonated long after the war’s end.

Mr. Hirabayashi and his fellow Japanese-Americans Fred Korematsu and Minoru Yasui, who all brought lawsuits before the Supreme Court, emerged as symbols of protest against unchecked governmental powers in a time of war.

“I want vindication not only for myself,” Mr. Hirabayashi told The New York Times in 1985 as he was fighting to have his conviction vacated. “I also want the cloud removed from over the heads of 120,000 others. My citizenship didn’t protect me one bit. Our Constitution was reduced to a scrap of paper.”

In February 1942, two months after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in the name of protecting the nation against espionage and sabotage, authorized the designation of areas from which anyone could be excluded. One month later, a curfew was imposed along the West Coast on people of Japanese ancestry, and in May 1942, the West Coast military command ordered their removal to inland camps in harsh and isolated terrain.

Mr. Hirabayashi, a son of Japanese immigrants, was a senior at the University of Washington when the United States entered World War II. He adhered to the pacifist principles of his parents, who had once belonged to a Japanese religious sect similar to the Quakers.

When the West Coast curfew was imposed, ordering people of Japanese background to be home by 8 p.m., Mr. Hirabayashi ignored it. When the internment directive was put in place, he refused to register at a processing center and was jailed.

Contending that the government’s actions were racially discriminatory, Mr. Hirabayashi proved unyielding. He refused to post $500 bail because he would have been transferred to an internment camp while awaiting trial. He remained in jail from May 1942 until October of that year, when his case was heard before a federal jury in Seattle.

Found guilty of violating both the curfew and internment orders, he was sentenced to concurrent three-month prison terms. While his appeal was pending, he remained at the local jail for an additional four months, then was released and sent to Spokane, Wash., to work on plans to relocate internees when they were finally released.

His appeal, along with one by Mr. Yasui, a lawyer from Hood River, Ore., who had been jailed for nine months for curfew defiance, made its way to the Supreme Court. In 1943, ruling unanimously, the court upheld the curfew as a constitutional exercise of the government’s war powers. Mr. Hirabayashi served out his three-month prison term at a work camp near Tucson.

The Supreme Court declined to rule at the time on Mr. Hirabayashi’s challenge to internment as well. (Mr. Yasui had contested only the curfew.) But in December 1944, in a case brought by Mr. Korematsu, a welder from Oakland, Calif., the court upheld the constitutionality of internment in a 6-to-3 vote.

Mr. Hirabayashi later spent a year in federal prison for refusing induction into the armed forces, contending that a questionnaire sent to Japanese-Americans by draft officials demanding a renunciation of any allegiance to the emperor of Japan was racially discriminatory because other ethnic groups were not asked about adherence to foreign leaders.

The Hirabayashi, Yasui and Korematsu cases were revisited in the 1980s after Peter Irons, a professor of political science at the University of California, San Diego, found documents indicating that the federal government, in coming before the Supreme Court, had suppressed its own finding that Japanese-Americans on the West Coast were not, in fact, threats to national security.

In September 1987, a three-member panel of a federal appeals court in San Francisco unanimously overturned Mr. Hirabayashi’s conviction for failing to register for evacuation to an internment camp and for ignoring a curfew. The convictions of Mr. Korematsu and Mr. Yasui had been overturned earlier.

Federal legislation in 1988 provided for payments and apologies to Japanese-Americans who were interned during World War II.

Read the full article here.

The ACLU remembers Gordon Hirabayshi as an American hero and recipient of the Roger Baldwin Medal of Liberty - its highest award. Learn More

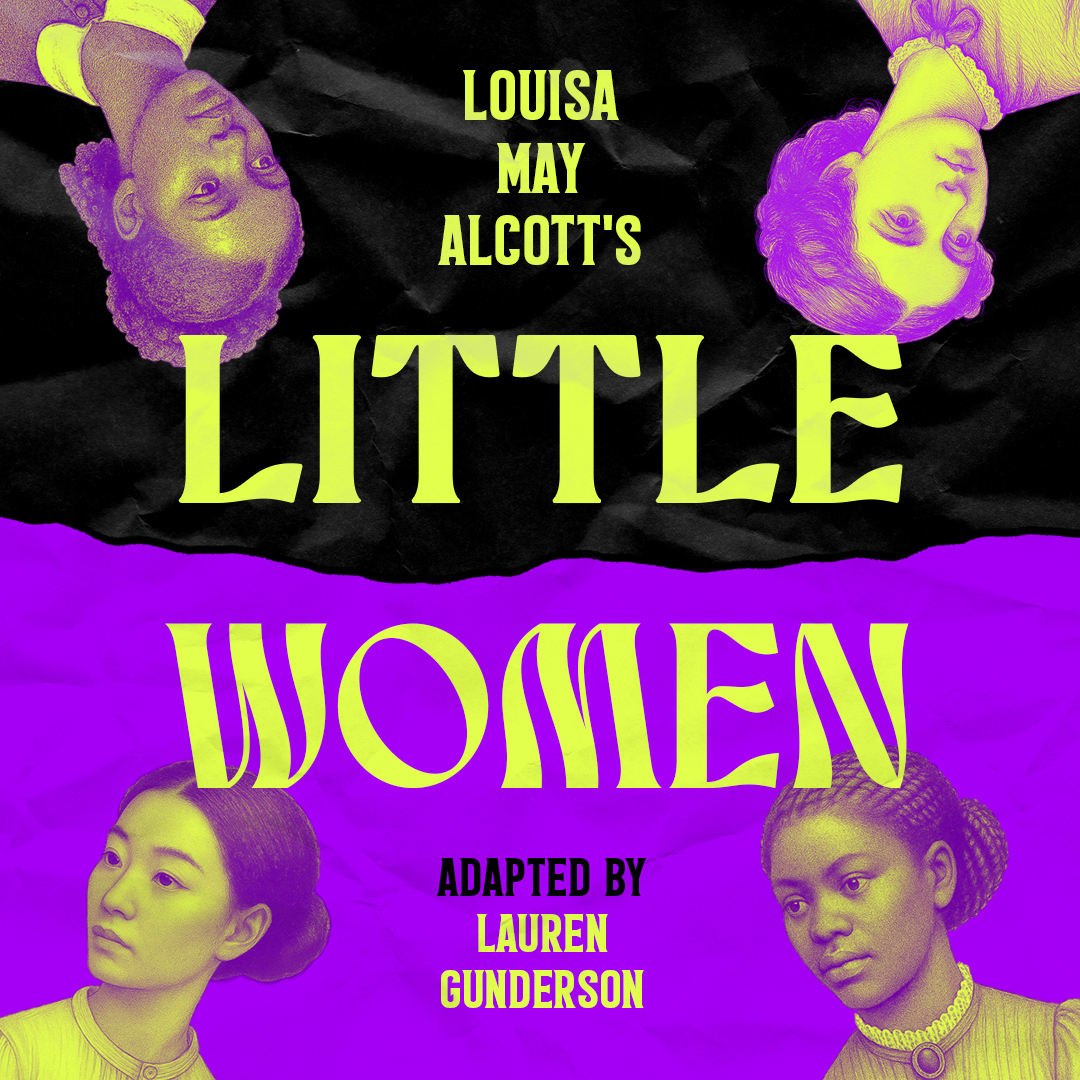

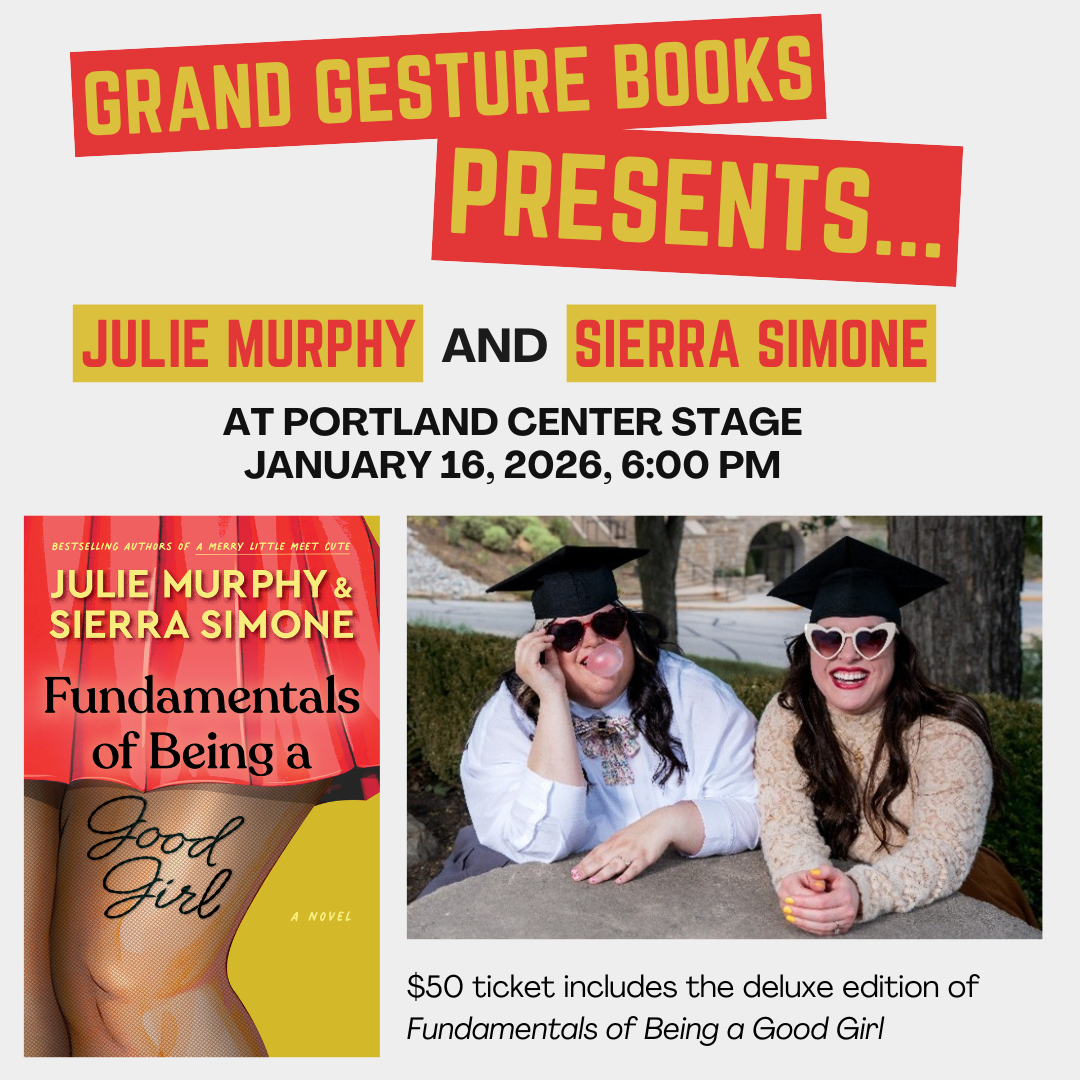

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).