The World of the Play: Coriolanus' Rome

Plutarch

The history of Rome is as mythical as it is factual and many of the things we hold as true about the rise and fall of the empire are speculative. Because there are few, incomplete and often conflicting written narratives about Roman society, history, governments and customs, a lot of what we assume to be true can be refuted. The accounts that follow here are to be read with this knowledge.

Situated on the Tiber River in central Italy, Rome grew from a city to an empire over the course of centuries. After Romans defeated the native Etruscians in battle in the 4th century B.C., they established a new governmental structure of a loose confederation of independently operating cities that all answered to the Senate to varying degrees. There is belief that for a time, a succession of six kings ruled this confederation but around 510 B.C. these kings were replaced by two elected officials (consuls).

Governmental Structure

Senate:

A body of several legislative assemblies. Each assembly had a different purpose. For example:

- Comitia Centuriata — This body decided about war, passed laws, elected magistrates (consuls, praetors, and censors), considered appeals of capital convictions, and conducted foreign relations.

- Concilium Plebis — This body elected its own officials and formulated decrees for observance by the plebeian class; in 287 B.C.E., it gained the power to make all decrees binding for the entire Roman community.

- Comitia Tributa — The tribal assemblies, open to all citizens (who only could be free, adult males), elected minor officials, approved legislative decisions often on local matters, and could wield judicial powers but could only levy fines rather than administer punishment.

Consuls:

Two officials elected by the legislative assemblies (senate members). They served year long terms and were essentially Heads of State who presided over the senate — think executive branch, with less power — and commanded the Roman military. They were nominated by the senate, then the people cast their votes, and then the senate ratified their appointment with another vote – think the Electoral College system.

Voting

Romans voted in a couple of different groupings: by a tribe and by centuria (century). Each group, tribe or centuria had one vote. This vote was decided by majority vote of the constituents of said group (tribe or centuria), so within the group, each member's vote counted as much as anyone else's, but not all groups were equally important.

Candidates, who were voted on together even when there were multiple positions to fill, were counted as elected if they received the vote of one-half of the voting groups plus one, so if there were 35 tribes, the candidate won when he had received the support of 18 tribes.

490 B.C., a Famine

According to historian Nathaniel Hooke, a fierce famine hit the Roman republic in 490 BC. He states: Under the following administration of T. Geganius and P. Minicuis, Rome was terribly afflicted by a famine, occasioned chiefly by the neglect of ploughing and sowing during the late troubles…The senate dispatched agents into Hetruria, Campania, the country of the Volsci and even into Sicily to buy corn. Those who embarked for Sicily met with a tempest…At Cumea, the tyrant Aristodemus seized the money brought by the commissaries…The Volsci, far from being disposed to succor the Romans would have marched against them, if a sudden and most destructive pestilence had not defeated their Purpose. In Hetruria alone the Roman commissaries met with success. They sent a considerable quantity of grain from thence to Rome in barks; but this was in a short time consumed, and the misery became excessive: the people were reduced to eat anything they could get…

This is the scene that the real Coriolanus met. It is said that he said that the people should not receive grain unless they would consent to the abolition of the office of tribune. For this the tribunes had him condemned to exile. Coriolanus then took refuge with the King of the Volsci and led the Volscian army against Rome, turning back only in response to entreaties from his mother and his wife. He died among the Volsci. Though Gnaeus Marcius did exist and did become Coriolanus, many people believe this story to be only legend and some believe it to be fact.

The First Plebeian Revolt

Several times in Rome’s history, the plebeian’s discontent for patrician rule led to revolts. The first, which began c. 494 B.C., was said to be in response to the laws that forced debtors into either enslavement or military service. Senators disagreed on how to handle the uprising. While some thought the solution was to forgive all debts, others suggested only forgiving the debts of war veterans and others still contended that a dictator be installed to quell the plebeians — forcing them into enslavement and service without forgiving their debts at all. This last proposal won out and Manius Valerius became the dictator of Rome. Valerius, however, gained the loyalty of the people by helping defeat foreign enemies, including the Volsci. Once he stepped down from his dictatorship, the patricians sought to reestablish hold over the plebs who swore no allegiance to the Senate and physically left the city, seceding from Rome led by Sicinius.

For months they lived apart, causing the Roman aristocracy to fend for the city on their own. Eventually, they sent Agrippa Menesius to convince them to return to the city. Some scholars say they were persuaded by a speech which compared Rome to the body, and describing the plebs as the limbs and the patricians as the head, as Shakespeare recreates in Act I. He also negotiated to give them power by creating two new tribune offices to represent them in government.

It is believed that under this new government structure that the “real” Coriolanus rose and fell from power. The plebs returned to Rome, but operated many extra-legal avenues of justice. According to scholar Christopher Schley Saladin:

This period brought a new political back and forth between the patricians and plebs that

our sources highlight through mostly fictitious episodes. Yet, some of the political conflicts they depict probably reflect actual conflict between patricians and plebs. The first of these conflicts involved the legendary patrician war-hero Marcius Coriolanus, who betrayed the city of Rome after being put on trial for wronging the plebs. Coriolanus’ story is mostly fiction, but the trial in which a tribune attempted to prosecute him may be based on an actual trial. In reality, this trial, and others against patricians by tribunes, were probably more attempted mob lynchings than legal court proceedings. Since none of these trials, including Coriolanus’, never came to fruition, they appear to have preserved extra-legal confrontations between patricians and plebs rather than formal trials. This highlights a denial of tribunal authority by the patricians, which reflects the extra-legal nature of the plebeian institutions and the inevitable conflicts that resulted from its attempted actions.

The Roman-Volscian Wars

The Romans and the nearby Volsci remained in intermittent conflict for approximately 200 years. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the Volsci were an: ancient Italic people prominent in the history of Roman expansion during the 5th century BC. They belonged to the Osco-Sabellian group of tribes and lived (c. 600 BC) in the valley of the upper Liris River. Later events, however, drove them first westward and then south to the fertile land of southern Latium.

The conflict began, according to both history and legend, during the reign of Rome's seventh and last king Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, when he took the wealthy town of Suessa Pometia, the spoils of which he used to construct the great Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus.

After a series of aggressions against the Romans by the Volsci, in 493 B.C., the Romans went on the offensive. They laid siege to the central Volscian city of Antium in a campaign led by the consul Postumus Cominius Auruncus and pushed their opponents into the neighboring city of Longula, capturing that city as well. At the same time, however, a second Volcsian force began a counterattack from the city of Corioli. This is where the legend of Coriolanus begins. Some scholars suggest that Shakespeare used this siege and Coriolanus’ heroic acts as a comment on his contemporary English army, who were moving away from such bravery and reprimanding officers who went rogue during missions.

Just two years later, Coriolanus would join the Volsci after his exile and lead a campaign against Rome by the Volscian leader Aufidius’ side. While they were initially successful and held their ground for several years, when disputes between the Volsci and their allies, the Aequi, who refused Aufidius as their leader, Rome was able to exploit their weakness and regain control of their lands in 487 B.C.

By 338 B.C. the Volsci had lost all of their land and power and became absorbed by the Roman Empire. While they attempted a few more rebellions after, they were ultimately unsuccessful.

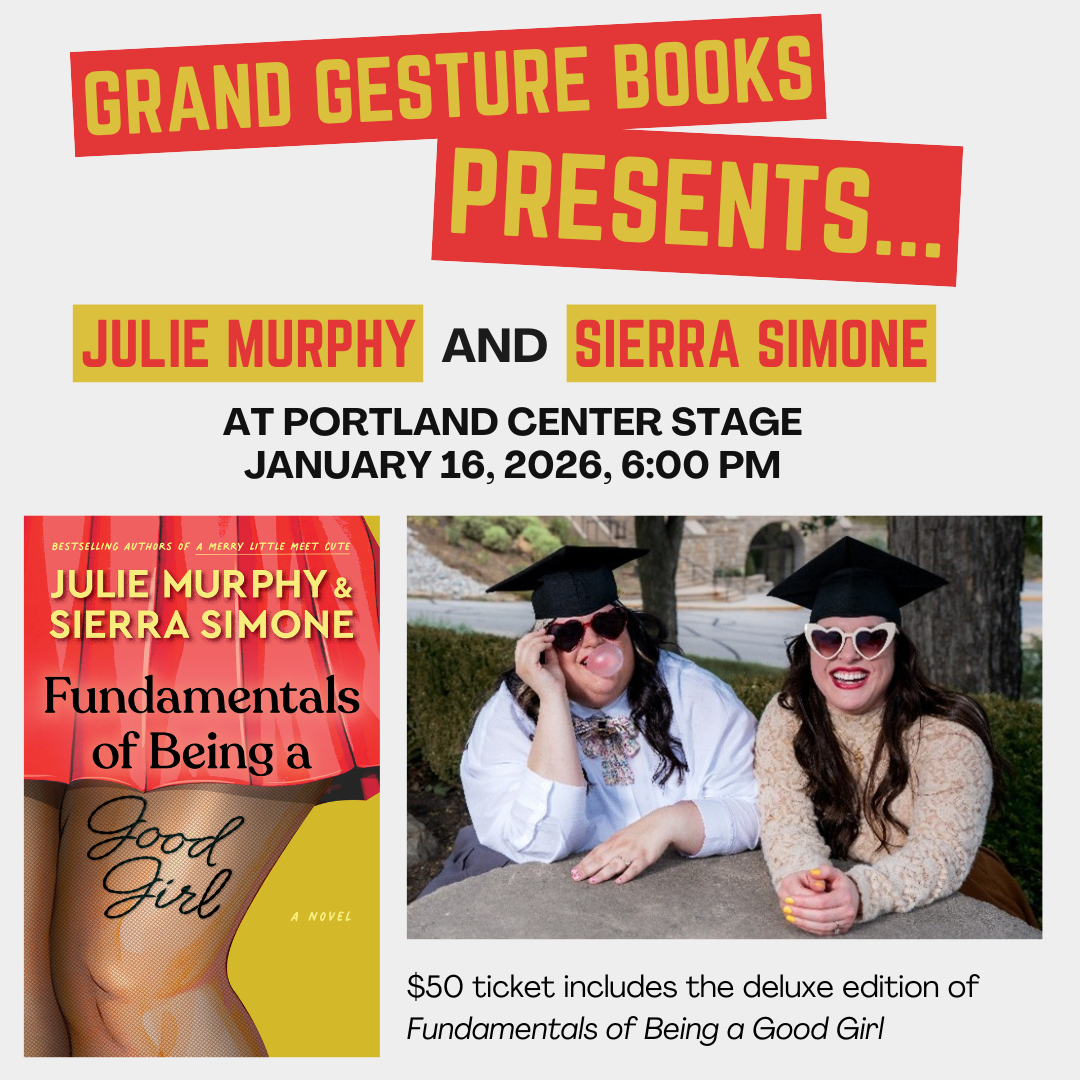

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).