Class and Fortune in "Great Expectations"

The world of Great Expectations is one in which fortunes can be suddenly made and just as suddenly lost. For the British Library, Professor John Bowen explores how the novel’s characters negotiate and perform class in this atmosphere of social and financial instability. Read the full article here.

Britain in the 19th century was an extraordinarily dynamic place, one that was pioneering new forms of social and urban organisation. People often think of Victorian society as a stratified one with rigidly fixed class identities, but Dickens' novels tell a very different story. Like Dickens himself, the characters in his stories often make huge social transitions, both from wealth to poverty and the other way round. He only wrote two novels in the first person. The first of these, David Copperfield (1848-50), tells a triumphant story of class mobility in its description of David’s progress through hard work and talent from poverty to success, wealth and happiness. Great Expectations tells a much darker and more haunted version of such a class transition. Both are novels focussed on psychological growth or development, but whereas the narrative movement of David Copperfield is towards fulfilment and insight, that of Great Expectations is to emptiness and loss of self.

Dickens' works portray a very mobile society in which fortunes can be made and just as suddenly lost. Some of his contemporaries, such as Karl Marx, believed that the social classes were being increasingly driven apart, divided into the two opposing camps of the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Dickens, by contrast, is fascinated not by the similarity of people in a particular class, but by their differences. He portrays in detail the extraordinary variety of ways, in small differences of clothing, accent and behaviour, by which people show and act out their class identities and aspirations. He is constantly drawn to characters who are at the margins, rather than the centre, of social classes: those clinging to the edges of gentility or respectability, and those who suddenly fall or rise in the uncertain world of the Victorian economy

Class as a performance

In Dickens’ work, it is often quite hard for characters to know for certain what class people belong to, or to be sure that they are who they claim to be. Class identity thus becomes a matter of performance, not linked in any essential way to the job that you do or the wealth that you have. This is particularly so in the urban encounters that he portrays. Class becomes something not given but created, a range or repertoire of performances and roles, each with different possibilities and dangers attached. Many of Dickens’ characters are performers who are unwilling simply to accept their given place in society but are determined to transform it into something different, better or more spectacular. This of course gives great scope for deceit, falsity and self-deception – and for comic misunderstandings.

The cruelty of class divides

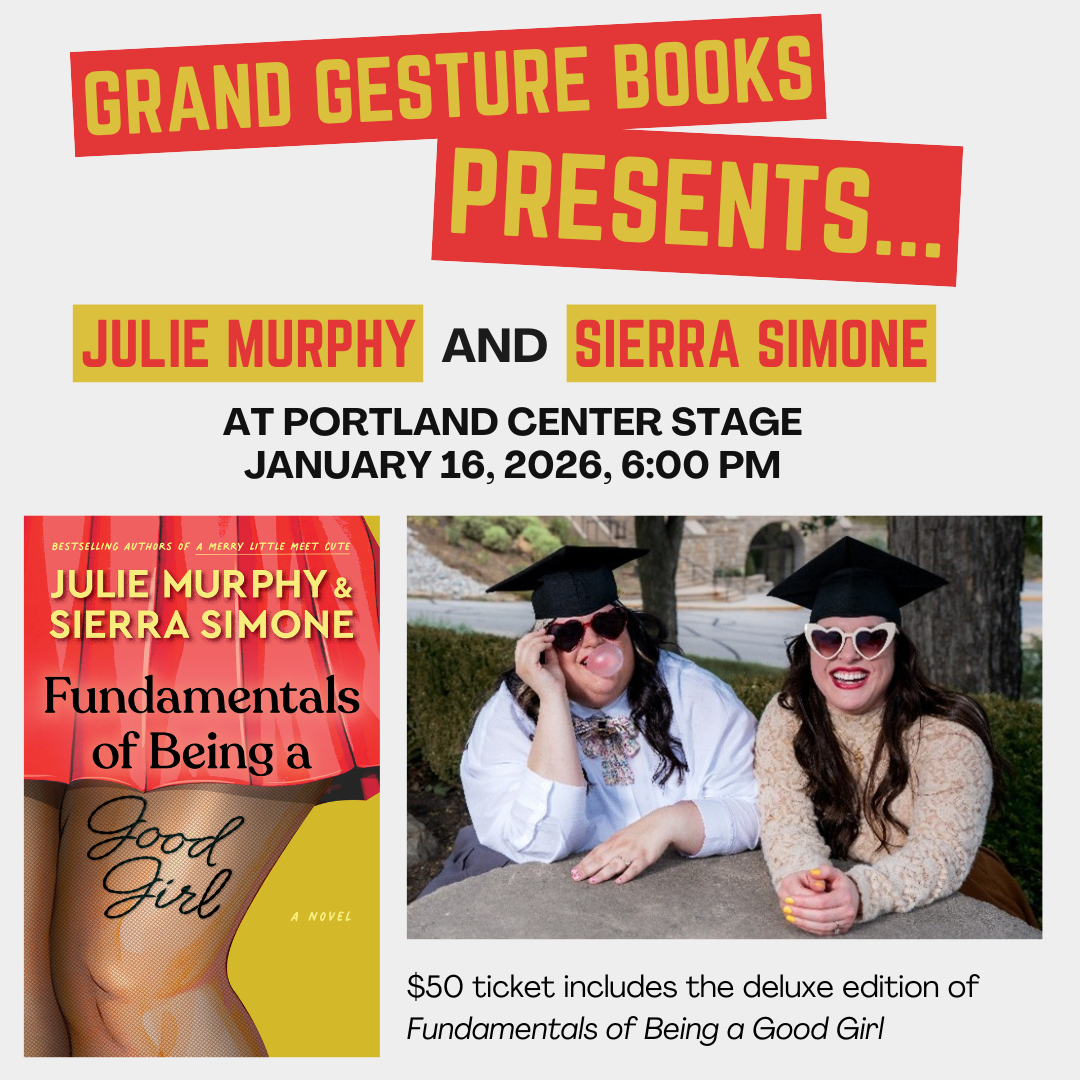

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).