Behind the Curtain: It’s a Wonderful Life: A Live Radio Play

PCS Literary Manager Kamilah Bush talks to Phil Johnson and Matt Rowning, the sound design and composition team, about bringing this unique experience to life.

One hundred years ago, the WGY Players from a radio station in Schenectady, NY, began to broadcast a weekly serialized program using a troupe of actors, sound effects, and music. The success of their program spread across the country quickly and soon cities across America were forming similar companies. By 1930, 14% of all radio programming was radio dramas. It’s a Wonderful Life: A Live Radio Play brings together a millennium of theatrical tradition and a century of broadcast tradition — along with its connection to the iconic film — into something quite singular.

Radio broadcasting had just begun and new forms of entertainment such as the radio melodrama were being invented for the new medium. In this image, WGY’s in-house acting troupe, the WGY Players, are broadcasting "The Great Divide." The scene depicted sounds of stifled cries paired with smashing effects — produced by wrecking a packing case, accompanied by a wood crash machine and sand board. The players are (L-R) Edward E. St. Louis, "Shorty"; Frank Oliver, "Dutch"; Edward H. Smith, "Steven Ghent"; and Ruth Shilling, "Ruth Jordan."

Kamilah Bush: It’s a Wonderful Life has a significant cultural footprint. What is your relationship to this story? In what ways are you looking to put your own mark on it, sonically?

Phil Johnson: Actually the first time I watched the movie was when I signed on to do this play. I was immediately able to recognize the plot and its cultural significance, I just had never actually seen it.

Matt Rowning: I admit it: I’d never seen the movie before! After getting to know it and its brilliant score, I knew immediately that we would not be able to replicate the big 1940s sound of the film onstage. Rather, the question became: “How do we create something beautiful with the pieces we have?”

KB: This production is unique, in that it is a radio play, meaning you will perhaps be incorporating many traditional audio elements into the design, but it’s also all happening on stage in front of an audience! What are the beauties and challenges of that?

PJ: Radio is an interesting aesthetic because it sounds maximalist, no matter what era you look at. When dealing with Foley*, it can get particularly tricky because you are using a wide range of gadgets and instruments to hint at sounds, rather than telegraphing them directly. On stage is even more difficult, because we have to trick your eyes and ears at the same time. The process is a lot of asking the question, “Is this for the audience's eyes or ears?”

MR: I think (and hope!) the audience will get as much joy as I do from watching a sound effect being generated live on stage. There’s this whimsical and fun nature to the radio-style Foley design they’ll see. For some, it may be distracting to watch the Foley happen. There is a compromise to be found between upstaging the action of the play with the live sound design and showing off the novel nature of Foley!

KB: The actors will play a major role in how this world sounds. How have you all approached the collaboration with each other and, ultimately, the cast in creating this audio world?

PJ: I think the relationship is based on trust and subtle nudges. We find sound devices and instruments we like and pass them to the actors and say, “I feel like it's kinda like this. Or what if you tried that on this instrument?” Then let them roll with it. They usually are better at finding the specific sound choice, but you still have to give them something to build off of.

MR: In the music composition and devising process, I’ve tried to bill myself as a support to the actors, to let them find what works for them, and not just stick music that I wrote in front of them. Devising music involves a lot of trust and a lot of quick math to put it all together. I hope they feel supported throughout our collaborative composing, and that I’ve pulled their arrangements together well.

KB: Where do you start a design or composition? Is there a particular window through which you typically find your way in?

PJ: I always start with a playlist. Music helps me envision the tone of a piece and begins the process of helping me shape the journey I want to take the audience on. From there, I begin to think of sounds and tones that complement the music that I'm listening to. I think about what relationship these sounds have with our daily life — are they relevant or relatable to the audience? After that, I remove the initial music to see what's left. What is the story we are telling? Finally, I find more music that relates to or emboldens that story. What we are left with is the design.

MR: Composition for me begins with an emotional “event.” This is some real or imagined scenario that prompts an emotional response that I explore with music. In the case of writing music for a play like this, there are added layers of both creating music that fits the period, and also the restriction of what instruments we have access to and what skill levels our actors bring to each instrument. All of these coalesce into the first musical ideas I’ll bring to the actors and director, and then we get to explore them together!

*Fun Fact: The term "Foley" originates from the late 1920s when sound was first introduced in feature films. Jack Donovan Foley and his sound crew developed a unique method for performing sound effects live, in synchrony with the film, during post-production. Sound effects that were created live for radio broadcasts existed much earlier, and they were known simply as live sound effects. While "Foley" is now commonly used for both types of sound effects, the term is specific to film.

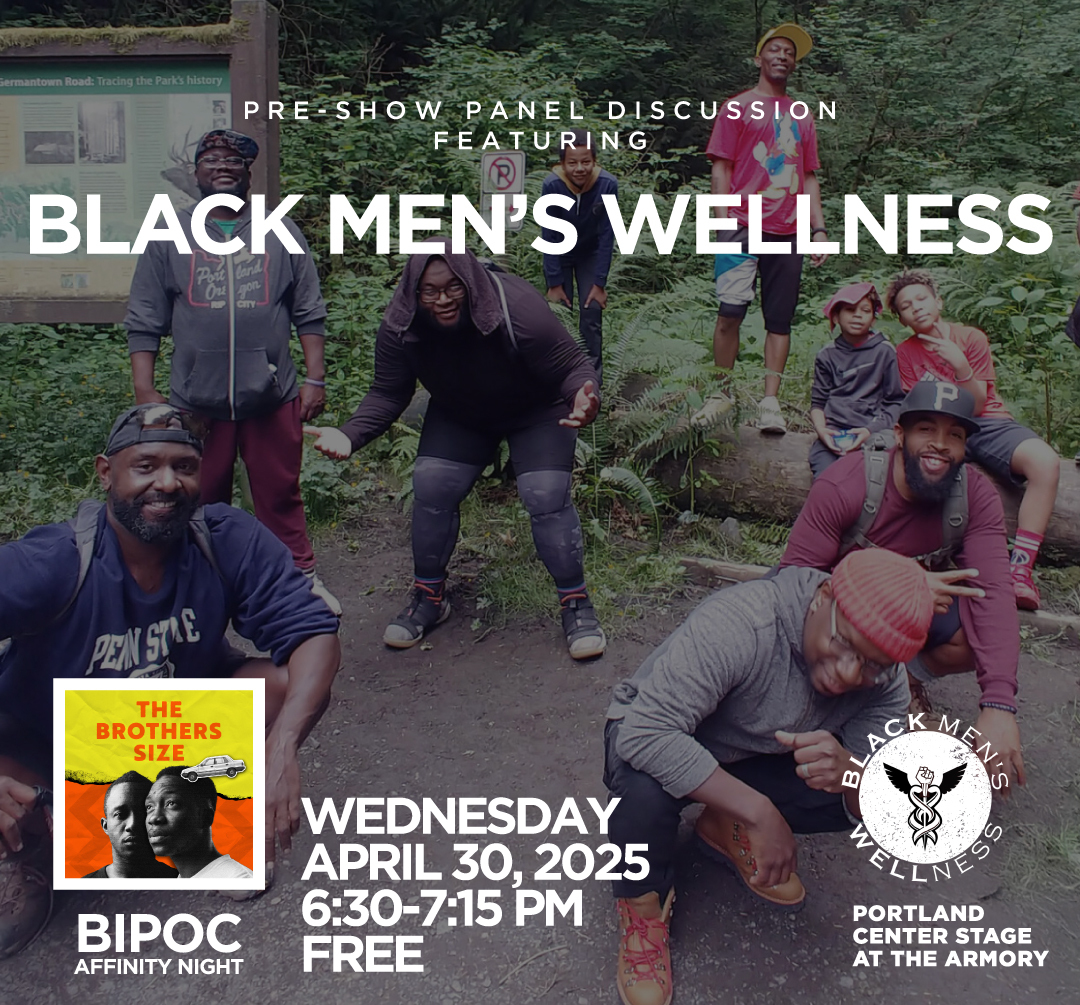

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).