Albee's Absurdity

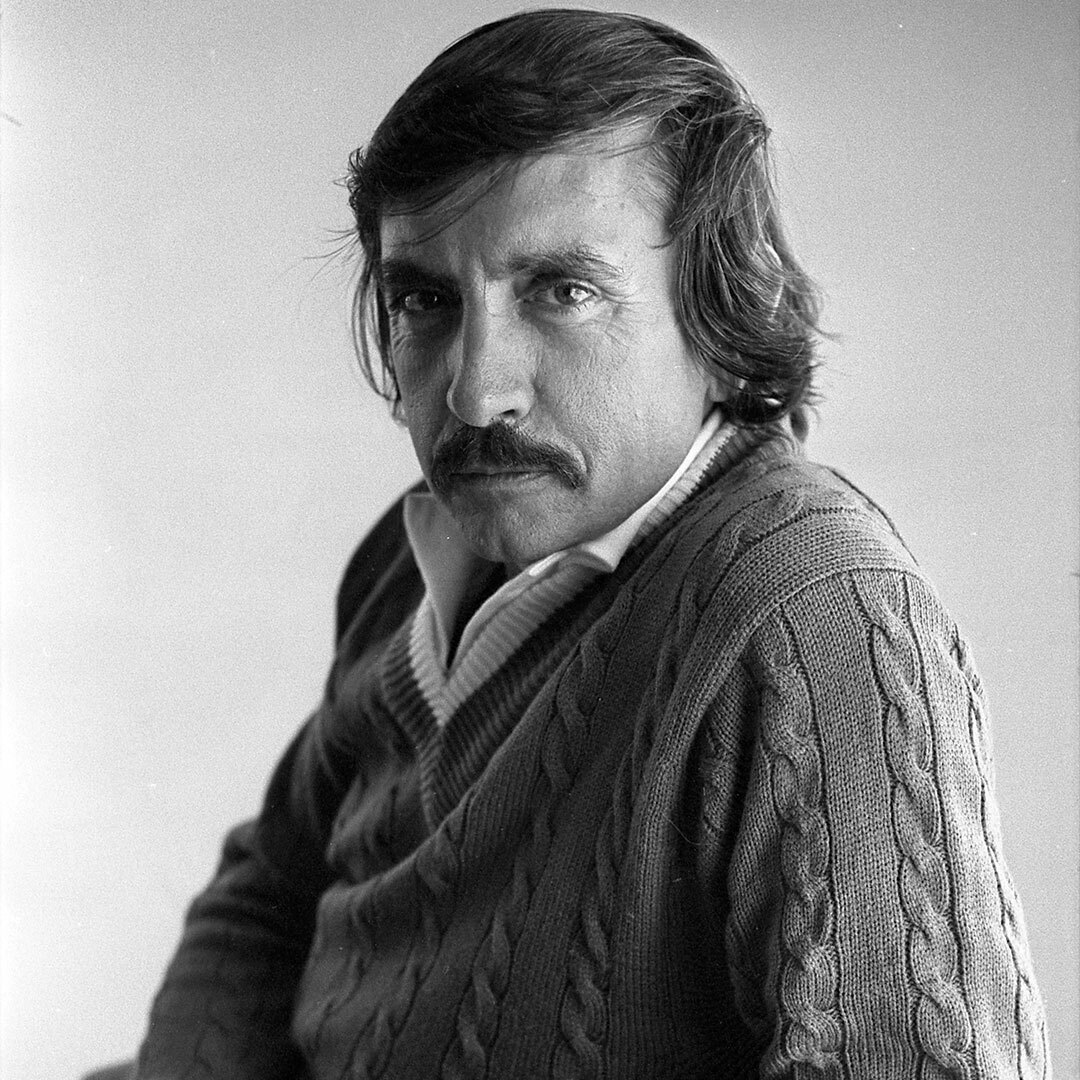

Edward Albee

In the settling dust of a remade world, and the churning possibilities of rights movements across the globe, emerged in artists and philosophers a sentiment that on the surface is bleak and pessimistic: life and everything in it is absurd. Beginning in Europe the later half of the 1940s and rolling right into the 60s, Theatre of the Absurd was a wave of plays influenced by the Existentialist philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. In fact, the building blocks of the movement were Camus’ work The Myth of Sisyphus which asserts in its opening paragraph:

Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy. All the rest — whether or not the world has three dimensions, whether the mind has nine or twelve categories — comes afterwards. These are games; one must first answer.

Woof. Right? Bleak. But the Absurdists' attraction to this philosophical path was not rooted in despair. Frankly, perhaps the world had had enough despair as World War II gave way to The Cold War, the Korean War, the war in Vietnam — the Absurdists instead saw this as a confrontation of self. The truth, however harsh, must be faced if life is to be worth living.

Edward Albee’s canon grew from this movement, alongside writers like Samuel Beckett, Eugene Ionesco and María Irene Fornés. A 1962 New York Times article, which reviewed both Beckett and Albee, speaks of the work:

In the Theatre of the Absurd the word absurd is not to be construed to mean ridiculous. Instead, it denotes what practitioners regard as the contemporary human condition. Bereft of illusions and certitudes, cut loose from faith and old values, man is lost and apparently devoid of purpose. His condition then is out of harmony with life, illogical, senseless, useless – hence absurd.

However, broadly speaking, the playwrights of the movement seek to stimulate their fellow man to face up to harsh reality and make the necessary readjustments. Then the old illusions will no longer be troublesome.

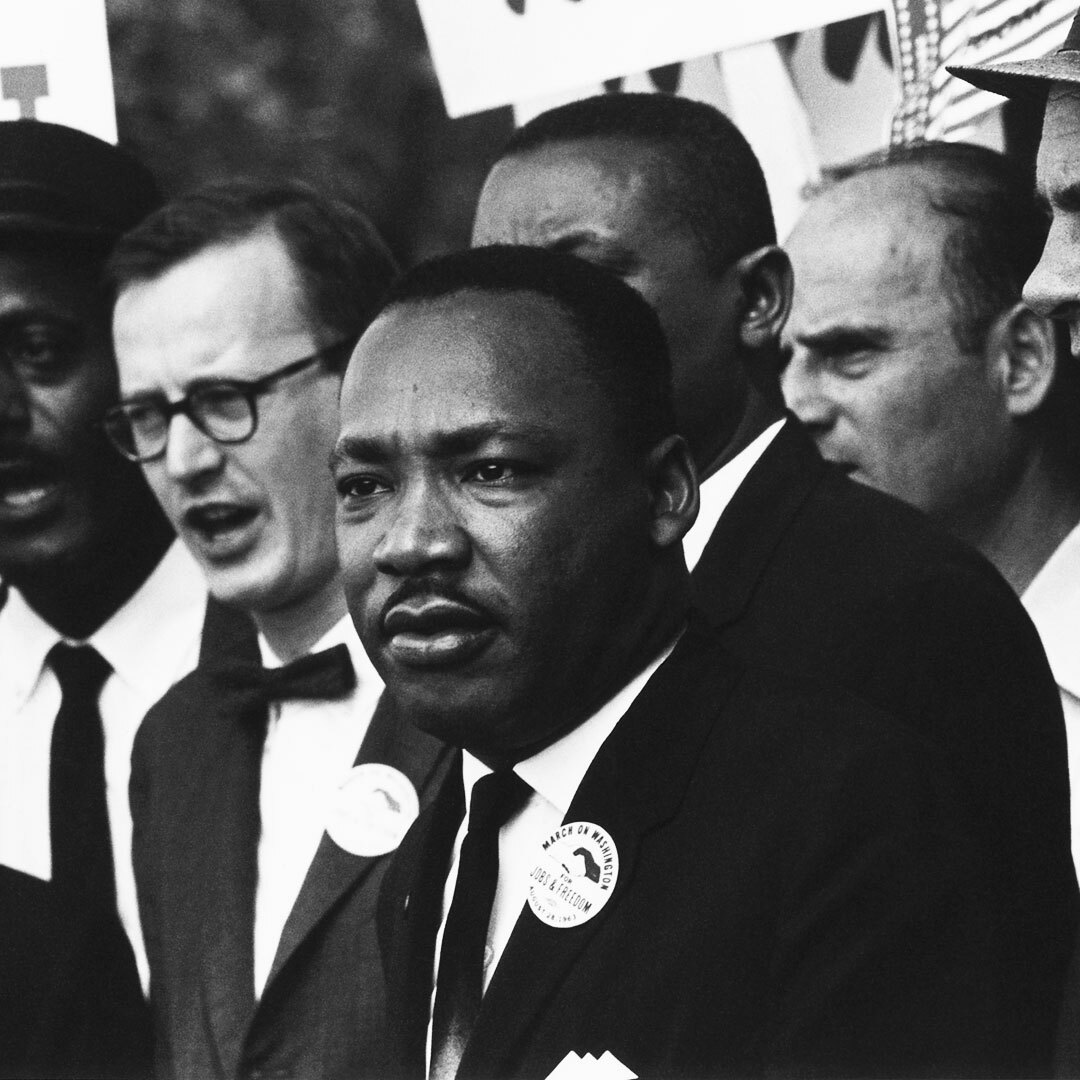

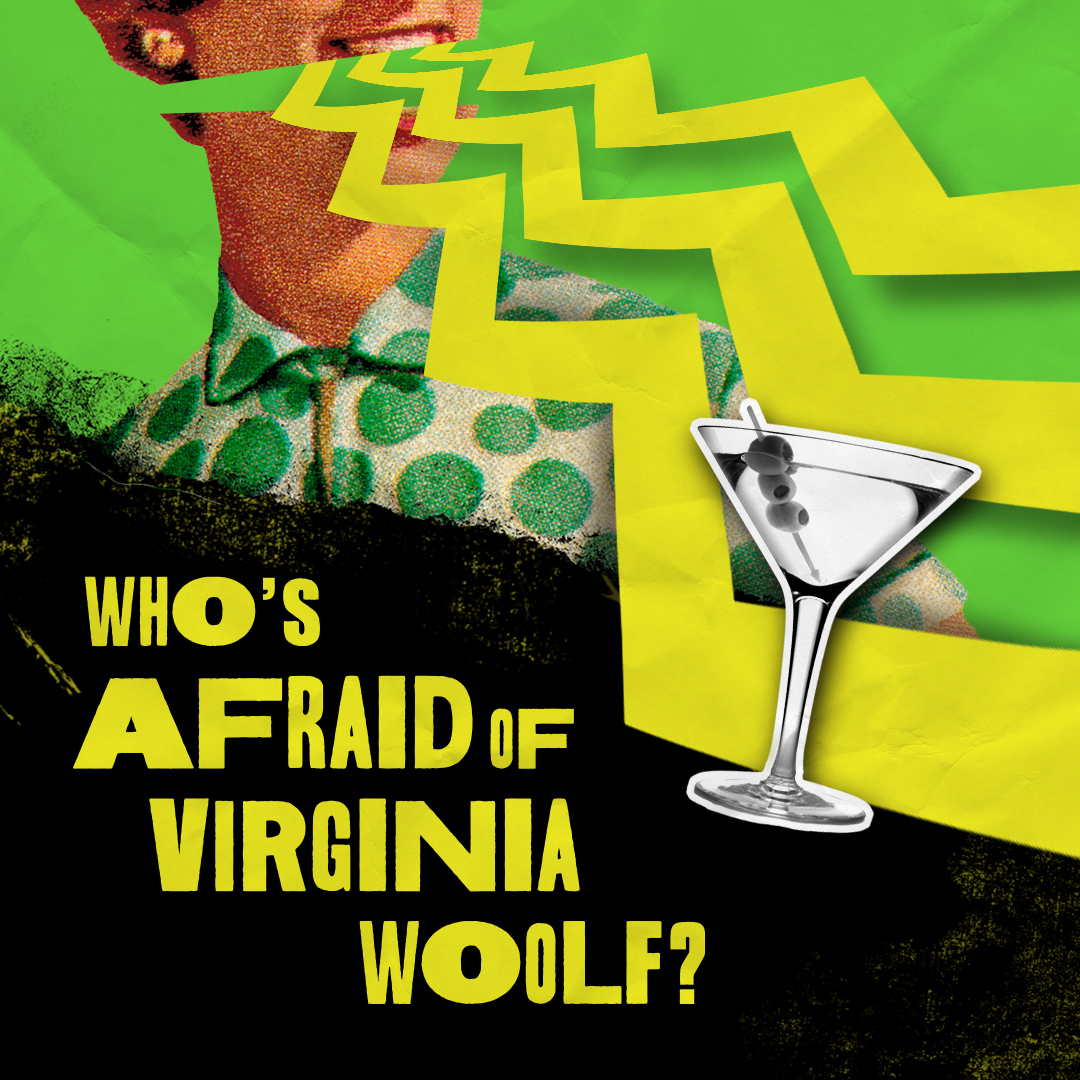

On stage, the elements of this movement are marked by nontraditional storytelling, alienation, disorientation, failure to communicate and existentialism. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? employs these tactics in stunning relief. The central characters, George and Martha, have an awful lot to face over the course of this drunken party that lasts into the wee hours of the morning. On the surface, this can seem a critique of love and marriage, but as Albee’s work insists, the criticisms aim much higher. This satire is not just a takedown of tumultuous relationships between husband and wife, but between citizen and society, settler and state, inhabitant and empire. Political theater, like the performance of domesticity — like life — is as absurd as anything else. All of this may, in fact, be absurd but as the writer James Baldwin states, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” And so, Edward Albee asks us, like George and Martha, to face the dawn.

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).