A Brief History of Christmas

Before Christianity began to spread across the European continent, there were several mid-winter celebrations in existence. These pagan — and in this case pre-Christian — festivals were vaguely similar across several cultures. The Romans celebrated Saturnalia, a festival characterized by drinking ale, gambling, and games, the eternal burning of candles and fires, a large feast, and the temporary dissolution of the class structure. During Saturnalia, there was no slave, no master, no rich, no poor, and all people came together to celebrate as equals. Northern Europeans (who would now be Scandinavian, German, etc.) celebrated Jul or Yule. This festival very closely resembled Saturnalia, where participants feasted on meats, drank wines and ales, burned fires and candles, and made ritual sacrifices of animals to their ancestors.

As Christianity spread, Christmas was adopted to encourage conversion — those people who were used to participating in these pagan holidays could continue most of the practices, but now in the name of the Christian God. Some of these practices survived — very often Christmas is celebrated with a large family dinner, the lighting of fires and candles (or at least some festival of lights), and a feeling of community and togetherness, regardless of social/economic status. Though Christmas, religiously, celebrates the birth of Christ, the date of Christ's birth and Christmas most likely do not coincide. The mid-winter celebration of Christmas only comes as a direct result of the co-opting and erasure of pagan practices.

How the specific date of December 25 was selected is not confirmed, but likely came from negotiations between the Eastern Christian Churches of modern-day Egypt, Syria, Turkey, and Greece, who primarily celebrated Epiphany (which occurs on Jan. 6) and the Western Christian Church, which included Northern Africa and Southern Europe. December 25 likely comes from the date Constantine came to power, ending the persecution of Christians.

The Roman Philocalian Calendar has the first mention of December 25 as the date of the birth of Christ but contains no mention of Epiphany. As Roman Christianity spread throughout the 300s and 400s, the Eastern and Western philosophies merged. Both churches adopted December 25 as Christmas, which celebrated the birth of Christ, and January 6 as Epiphany, which focused on the coming of the Magi.

The Invention of Christmas

Knowing its roots in paganism, Puritans during the 17th century waged a war against Christmas, and when they gained power during the English Revolution they outlawed the holiday celebrations. Puritans who came to the Americas also held these views, and observing Christmas carried a fine of five shillings. Larger English society adapted to a Christmas-less calendar year and historians document that nearly an entire generation of children grew up without even an idea of what Christmas could be. Christmas was still celebrated, quietly, by some English people and it never truly died out in other parts of the world, such as, notably, Germany.

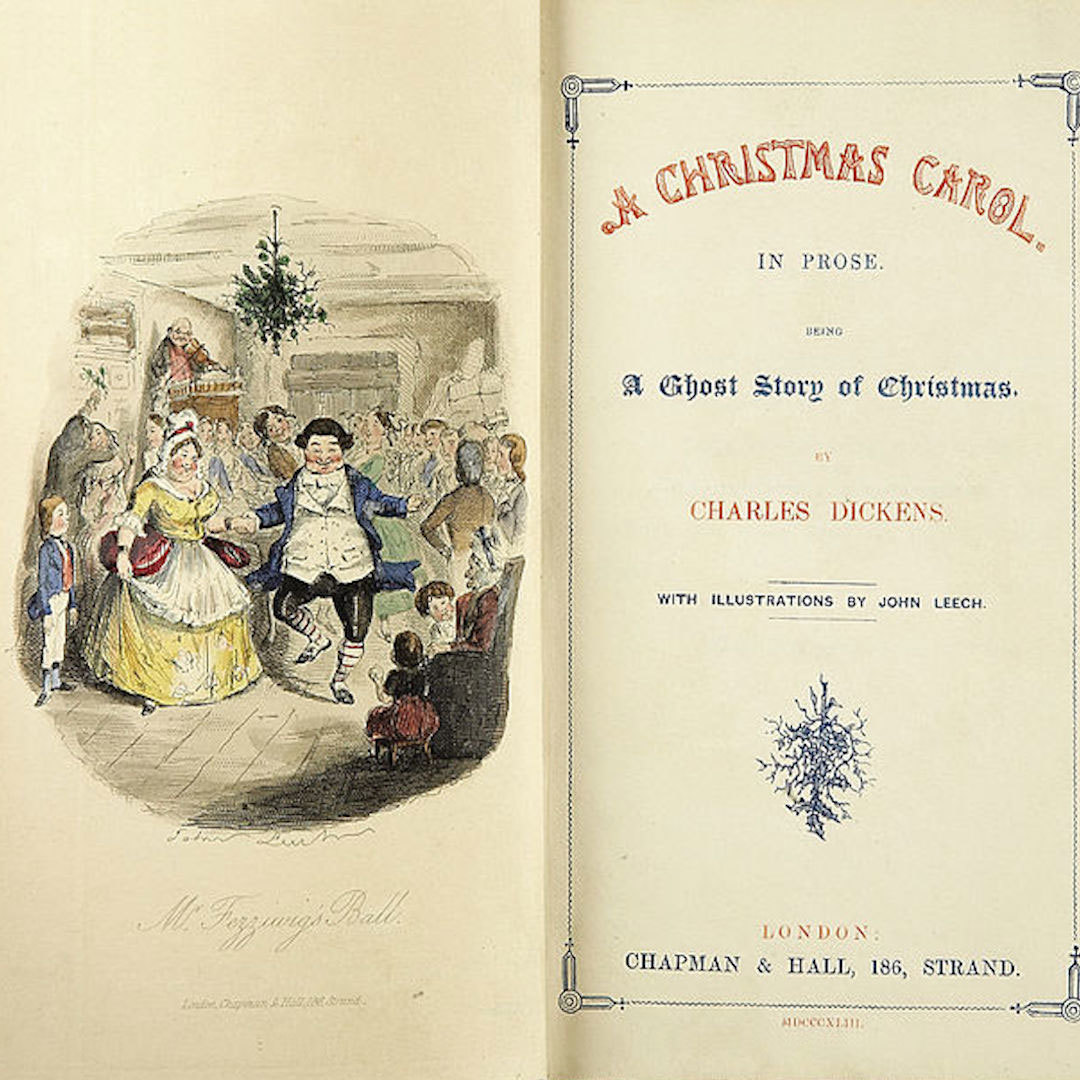

Charles Dickens in 1858; photo by Herbert Watkins.

In 1843, Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol was published, and while it may seem to modern readers that this novella was a picture of a Victorian Christmas, it was not very representative of what Dickens experienced during Christmas at all — rather what he imagined it could be. As audiences delighted in his ghost tale, they also became enchanted with this idea of a Christmas that focused on family, charity, celebration, and goodwill. Dickens never mentioned Christ in his account of Christmas, he only tangentially mentions that the reformed Scrooge "also went to church." It is from this novella that we get such phrases as "Merry Christmas" and "Bah! Humbug" and that “miser” and “Scrooge” became synonymous. The idea of not working on Christmas also comes from Dickens, as well as the tradition of eating turkey for Christmas dinner and the extolling of the "Spirit of Christmas."

It may be a mere coincidence that in the same year, at the same Christmas, the first Christmas card was created and sent. Once Queen Victoria had received one, she became infatuated with the idea and spent many Christmases following creating them with her children. The young queen was married to the German-born Prince Albert. In his native country, there had been no Puritan suppression of Christmas, and he was used to not only celebrating Christmas but also having a Christmas tree. He brought this tradition with him to England and, as Dickens' newly romanticized Christmas took hold, so did this symbol of the holiday — especially when, in 1848, two days before Christmas, the royal family appeared next to their Christmas tree in the Illustrated London News.

The royal Christmas tree is admired by Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their children, December 1848. A Christmas tradition stemming from Saturnalia was the Christmas tree: During the winter solstice, branches served as a reminder of spring — and became the root of our Christmas tree. The Germans are credited with first bringing evergreens into their homes and decorating them, a tradition that made its way to the United States in the 1830s. But it wasn't until Germany's Prince Albert introduced the tree to his new wife, England's Queen Victoria, that the tradition took off. The couple was sketched in front of a Christmas tree in 1848 — and royal fever did its work.

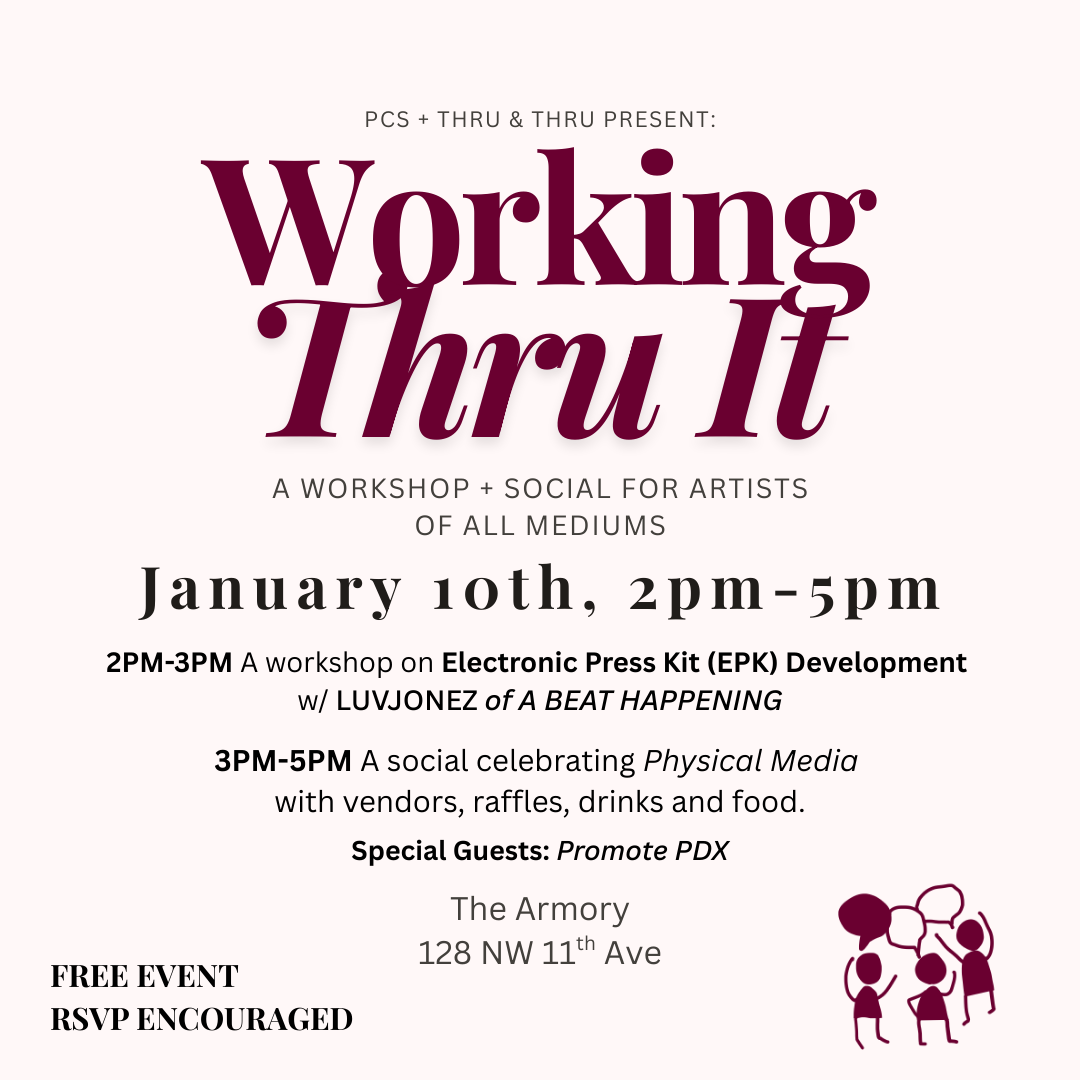

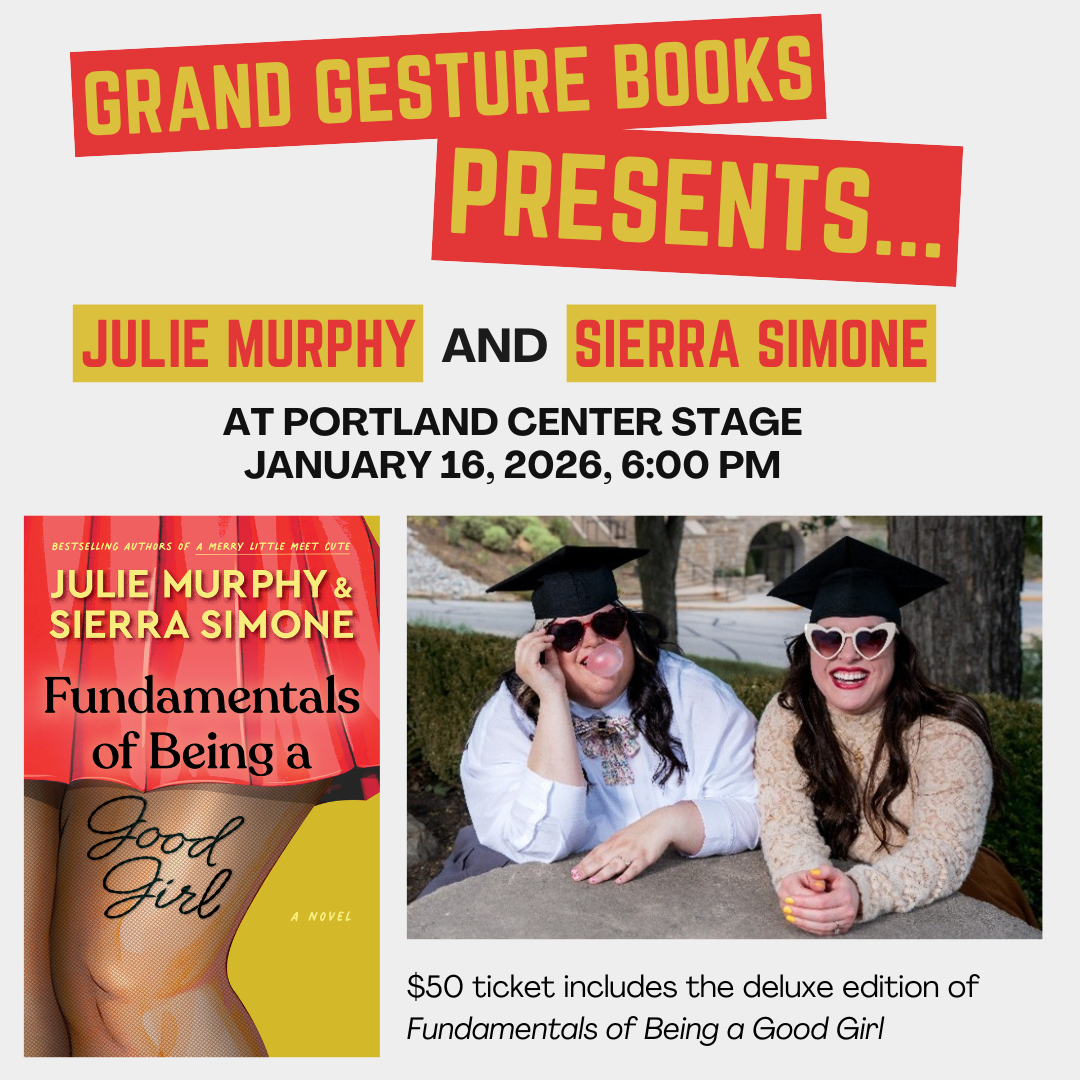

Portland Center Stage is committed to identifying & interrupting instances of racism & all forms of oppression, through the principles of inclusion, diversity, equity, & accessibility (IDEA).